Home » General Geology » Glaciers

Glaciers

Article by Sara Bennett, geology instructor at Western Illinois University.

Bucher Valley Glacier in Alaska beautifully represents a large glacier that receives ice from multiple smaller glaciers that join it like the tributaries of a stream. Image by the United States Geological Survey.

What is a Glacier?

A glacier is a slowly flowing mass of ice with incredible erosive capabilities. Valley glaciers (also known as alpine glaciers or mountain glaciers) excel at sculpting mountains into jagged ridges, peaks, and deep U-shaped valleys as these highly erosive rivers of ice progress down mountainous slopes.

Valley glaciers are currently active in Scandinavia, the Alps, the Himalayas, and on the mountains and volcanoes along the west coasts of North and South America. The amazing, jagged landscape of the Southern Alps in New Zealand is also courtesy of the erosive power of glaciers. The lighting of the signal beacons in the movie The Lord of the Rings – The Return of the King [1] captures this famous landscape.

Continental glaciers (ice sheets, ice caps) are massive sheets of glacial ice that cover landmasses. Continental glaciers are currently eroding deeply into the bedrock of Antarctica and Greenland. The vast ice sheets are incredibly thick and have thus depressed the surface of the land below sea level in many locations.

For example, in West Antarctica the maximum ice thickness is 4.36 kilometers (2.71 miles) causing the land surface to become depressed 2.54 kilometers (1.58 miles) below sea level! [2] If all the glacial ice on Antarctica were to melt instantaneously, all that would be visible of Antarctica’s land surface would be large and small landmasses with scattered islands surrounded by the Southern Ocean

Southern Greenland from Space: A small continental glacier covers Greenland. Satellite image by NASA and the United States Geological Survey.

Sampling Glacial Ice: A scientist collects snow samples from the Taku Glacier of Alaska. Image by the United States Geological Survey.

How Do Glaciers Form?

A considerable amount of snow accumulation is necessary for glacial ice to form. It is imperative that more snow accumulates in the winter than that which melts away during the summer. Snowflakes are six-sided crystals of frozen water; however, layers of fluffy snowflakes are not glacial ice…not yet at least.

As thick layers of snow accumulate, the deeply buried snowflakes become increasingly more tightly packed together. The dense packing causes the snowflakes to take on rounded shapes as the six-sided snowflake shape is destroyed. With enough time, the deeply buried, well-rounded grains become very densely packed, expelling most of the air trapped between the grains. The granular snow grains are called firn and take approximately two years to form. [3]

The thick, overlying snowpack exerts tremendous pressure onto the layers of buried firn, and these grains begin to melt a tiny bit. The firn and meltwater slowly recrystallize, forming glacial ice. This transformation process may take several decades to hundreds of years because the rate of glacial ice formation is highly dependent upon the amount of snowfall. (The recrystallization process means that glacial ice is really a type of metamorphic rock.)

Tazlina Valley Glacier: Crevasses are visible near the thinning terminus in the zone of wastage. Note that the ice surface is dirty due to the accumulation of sand and gravel particles. Tazlina Valley Glacier in Alaska is retreating. Image by Bruce F. Molnia, USGS. Click the image to enlarge.

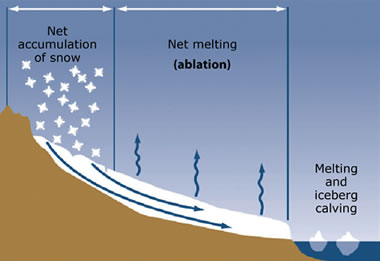

Zones of a Glacier: A cartoon cross-section through a glacier, showing the zone of accumulation and zone of wastage. Image by the United States Geological Survey.

How Do Glaciers Flow?

A glacier begins to flow when a thick mass of ice begins to deform plastically under its own weight. This process of plastic deformation (internal deformation) occurs because the ice crystals are able to slowly bend and change shape without breaking or cracking. Plastic deformation occurs below a depth of 50 meters (164 feet) from the surface of the glacier. [4]

Thick glacial ice is quite heavy, and the great weight of the glacier may cause the ice along the base of the glacier to melt. Melting occurs because the temperature at which ice melts is reduced due to the pressure exerted by the weight of the overlying glacial ice.

Heat from the Earth’s surface may also cause ice to melt along the base of the glacier. The process of basal sliding occurs when a thin layer of meltwater accumulates between the basal ice and the Earth’s surface. The meltwater functions as a lubricant allowing the glacier to slide more readily over bedrock and sediments.

If a great deal of slippery meltwater accumulates under the ice, the glacier may begin to advance very rapidly as a surge. Sometimes known as a galloping glacier, a surging glacier flows at a very rapid rate. For example, in the summer of 2012, Jakobshavn Glacier, located on the east coast of Greenland, was measured to be advancing at a rate of 46 meters per day (151 feet/day). [5] Jakobshavn Glacier is widely believed to be responsible for generating the large iceberg that ultimately sank the Titanic in 1912.

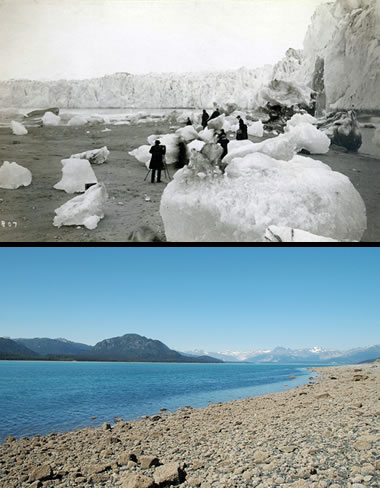

Before and After Photos: Photos taken at the same location location in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Alaska. The upper photo shows Muir Glacier in the 1880’s and the lower photo shows the same inlet in 2005. Muir Glacier has retreated 50 kilometers (31 miles). Both images by the United States Geological Survey.

What Are the Zones of a Glacier?

A glacier can be divided into two parts: 1) the zone of accumulation; and, 2) the zone of wastage.

Zone of Accumulation

The area of glacial ice formation is called the zone of accumulation. In this zone more snow accumulates each winter than that which melts away during the summer. Buried accumulations of snow turn into firn and eventually recrystallize into glacial ice.

Glacial ice flows away from the zone of accumulation when the thick ice deforms plastically under its own weight. In a valley glacier the ice flows downslope from the zone of accumulation, while for a continental glacier the ice flows laterally outward and away from the zone of accumulation.

Zone of Wastage

The area of a glacier that experiences a greater amount of melting than glacial ice formation is called the zone of wastage (zone of ablation). In this zone, as the ice melts away, bits of sand and gravel on the surface of the glacier are left behind. It is important to note that glacial ice is always replenishing this zone as glacial ice continues to flow from the zone of accumulation.

Snow Line

The line that separates the zone of accumulation from the zone of wastage is called the snow line (equilibrium line). The snow line may be visible at the end of summer between the clean icy surface of the zone of accumulation and the dirty, sediment-covered surface of the zone of wastage.

Zone of Fracture

The upper 50 meters of the surface of the glacier, where the ice does not undergo plastic deformation, is referred to as the zone of fracture. In this zone the ice is brittle and only deforms by cracking, breaking, and fracturing. Crevasses are fractures or breaks in the ice that may be hundreds of meters long and up to 50 meters deep. [4]

Terminus

The end or toe of the glacier is called the terminus and is part of the zone of wastage. When the terminus of the glacier flows into a body of water, the ice at the toe calves or breaks off to form floating chunks of ice called icebergs.

A Glacier Story About John Muir

John Muir wrote about one of his 1880 adventures in Alaska, when he and the camp dog, Stickeen, went on a lengthy hike up a valley glacier [6]. On the return trip their way was barred by crevasses, and John had to walk a considerable distance until he discovered a precarious, narrow ice bridge spanning a deep crevasse.

Understandably, Stickeen was quite reluctant to traverse the dangerous bridge of ice and John spent considerable time and effort coaxing the fearful dog to cross. Stickeen and John eventually returned safely to camp only to be accosted by his fellow campers who were quite upset with him. John had failed to let anyone know where he was going!

Cirques: Two cirques containing small valley glaciers are separated by an arête. Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Image by the United States Geologial Survey.

Why Do Glaciers Advance and Retreat?

Glaciers have a snow budget, much like a monetary bank account. The more money deposited into a bank account, the larger the account grows. However, if more money is removed than is deposited into the account, the amount of available money is much reduced. Glacial ice advancement and retreat is quite similar.

When more glacial ice forms in the zone of accumulation than that which melts away in the zone of wastage, the glacier will grow and advance. The terminus of an advancing glacier will progress farther away from the zone of accumulation and thus lengthen the glacier.

A glacier retreats when more ice melts away during the summer than that which forms during the winter. The glacier reduces in size as the ice in the zone of wastage melts. The retreating glacial ice never actually flows backwards; the ice simply melts away faster than is replenished from new glacial ice formation in the zone of accumulation.

If the amount of glacial ice formation in the zone of accumulation equals the amount of melting in the zone of wastage, then the glacier does not advance or retreat. While the ice within the glacier continues to flow away form the source toward the terminus, the toe of the glacier will stand stationary because the glacial ice budget balances between the two zones.

| Glacier References |

|

[1] The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King: Directed by Peter Jackson, Performed by Elijah Wood, Ian McKellen, and Viggo Mortensen, New Line Cinema and Three Foot Six, 2004, DVD.

[2] Antarctic Reference Map: published by The American Geophysical Society. [3] All About Glaciers: How are Glaciers Formed?: Article published on the National Snow and Ice Data Center website, last accessed July 2022. [4] Glacier: Article in the New World Encyclopedia, last accessed July 2022. [5] Further summer speedup of Jakobshavn Isbrae: I. Joughin, B.E. Smith, D.E. Shean, and D. Floricioiu; Brief Communication published in The Cryosphere, 2014, last accessed July 2022. [6] Travels in Alaska: John Muir, ReadaClassic.com, 172 pages, 2012. [7] At the Edge: Monitoring Glaciers to Watch Global Change: John Weier, article on NASA's Earth Observatory website, 1999, last accessed July 2022. [8] All About Glaciers: The Life of a Glacier: Article published on the National Snow and Ice Data Center website, last accessed July 2022. [9] Status of Glaciers in Glacier National Park: Information page published on the United States Geoloigical Survey website, last accessed July 2022. [10] Time on the Shelf: David Herring, article published on NASA's Earth Observatory website, 2005, last accessed July 2022. |

How Does Climate Change Affect Glaciers?

The production of greenhouse gasses (e.g., carbon dioxide and methane) is contributing to a slow increase in global temperatures worldwide. According to NASA scientists, glacial ice is now melting at higher rates than ever before. [7]

Small valley glaciers across the globe are the most vulnerable to global climate change. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, approximately ninety percent of all monitored glaciers are in retreat. [8] For example, in 1910 there were about 150 valley glaciers located within Glacier National Park in the United States. In 2010, there were only 25 active glaciers left, and some of these remaining glaciers are in danger of disappearing by 2030. [9]

Glacial ice in Greenland and West Antarctica is also vulnerable to climate change. For example, Greenland ice is experiencing higher melting rates, with record melting catalogued in 2002. If either all of Greenland’s glacial ice melted or the West Antarctic ice sheet melted, the sea level would rise by 5 meters (16 feet). [10] The overall trend in glacier retreat worldwide reflects the increase in global temperatures.

Glacial Landscape: Several small cirques are visible and each one is the zone of accumulation or birthplace of a small valley glacier. Two valley glaciers flow around a small horn and merge together to form a larger valley glacier. Once upon a time, the larger valley glacier flowed down the whole length of the valley, carving out a U-shaped valley. The glacier is in retreat because only a portion of the glacially carved, U-shaped valley contains ice. A meltwater stream issues from the glacier’s terminus and flows down the ice-free portion of the valley. Image from the Chugach Mountains, Alaska by Bruce F. Molnia, USGS

What Are Some of the Erosional Features Carved by Valley Glaciers?

Several landscape features of glacial erosion are described below. You can view the accompanying photograph to see examples of each.

A cirque is a small bowl- or amphitheater-shaped depression.

An arête is a narrow, steep, jagged ridge of eroded bedrock.

A horn is a pointed, ice-carved mountain peak surrounded by cirques and arêtes. (A famous horn in the Swiss Alps is the Matterhorn.)

A U-shaped valley forms when a valley glacier flows down a stream valley and the erosive power of the flowing glacier modifies the V-shaped stream valley into a flat, steep-walled U-shaped valley.

The next time you watch the lighting of the signal beacons sequence in the movie The Lord of the Rings – The Return of the King [1], try and identify some of these amazing erosional features.

About the Author

Sara Bennett teaches geology classes at Western Illinois University and enjoys hiking in national parks. She encourages everyone to go for walks in natural places and become immersed in the Earth’s beauty.

| More General Geology |

|

Spectacular Fossils |

|

What is the San Andreas Fault? |

|

Bubbles in Amber |

|

Geology Dictionary |

|

Igneous and Volcanic Features |

|

Fossils |

|

Diamonds |

|

Minerals |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|