Home » Minerals » Legal Aspects of Rock Collecting

Legal Aspects of Rock, Mineral, and Fossil Collecting

By Timothy J. Witt, J.D.

|

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Determining Rock, Mineral, or Fossil Ownership and Possession Part 3: Additional Conditions, Limitations, and Prohibitions on Rock Collecting |

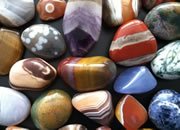

Much more valuable than a common pebble - if you are caught removing this without permission from almost any property that you do not own, and in some cases even a property that you do own, it could result in criminal or civil problems. Image copyright iStockphoto / Luftklick.

Part 1: Introduction

While fishing in a mountain stream, you find a small gold nugget. Is it yours to keep? Imagine digging in your backyard to install a new deck and unearthing several fossils. Do you own them? As you hike with your family in a national park on vacation, your children happen upon several small pieces of petrified wood. Are your children able to take them home? Picture yourself strolling on a long, sandy beach when your spouse's attention is caught by several beautiful stones gleaming under the shallow water. Can your spouse wade into the water to retrieve the stones and take them home as a souvenir? You and some friends are having a great day rock-climbing in a nearby state park when your activities reveal several interesting crystalline minerals. Is it legal for you to put them in your pack to show your non-climbing friends? In keeping these specimens, would the individuals have done something wrong?

These questions evoke fairly common and seemingly innocuous scenarios. Nonetheless, the question of legality underscores the legal framework in which such simple activities take place. Would someone be doing something illegal in keeping one of the found specimens? Quite possibly. Depending on a host of factors including the exact type, weight, and location of the specimens taken, someone may have subjected himself or herself to criminal and civil legal actions. Not following applicable laws when rock, mineral, and fossil collecting can result in serious consequences.1

Regardless of whether specimen collecting is referred to as rock hunting, rockhounding, or amateur geology, the legal issues associated with collecting remain the same. One of those issues cuts straight to the heart of the activity: is it legal? As with many legal questions, the answer is "it depends." And it really does just depend. The legalities of rock, mineral, and fossil collecting are multi-faceted and fact-specific. Questions about the legality of specimen collecting sit at the intersections of multiple areas of law, including real estate law, environmental law, mining law, and public law in both civil and criminal contexts. As a result, there are few easy answers, and many answers will be nuanced answers that are heavily-reliant on the particulars of individual instances of collecting. Without being trite, determining whether specimen collecting is legal or illegal in any given situation is a veritable "who-what-where-when-why-how" exercise. The purpose of this article is to explain many of the legal principles related to rock, mineral, and fossil collecting so as to enable specimen collectors to better evaluate the legality of their activities.

Signs like this on private property indicate that the property owner does NOT want people collecting agates on their land. There may be various reasons for this: They want to avoid potential liability, they simply don't want people on their land, they want the agates for their own personal use, or the agates are valuable. Believe it or not, some agates sell for a lot of money.

Some Basic Ground Rules

(No Pun Intended)

Rock, mineral, and fossil collecting is a popular hobby around the world and is not limited to any particular country or region. Indeed, many highly-sought specimens are available only in locales considered exotic or far-flung. Importantly, however, each area has a specific legal system applicable to that area; there is no single, uniform body of laws related to specimen collecting that applies across the globe.2 Accordingly, whether particular collecting activities are legal in one area does not mean that those same activities are legal in other areas. Given its likely audience, this article concentrates on the legal aspects of rock, mineral, and fossil collecting in the United States. Even within the United States, however, the legality of collecting involves state and local laws that could result in dramatically different outcomes despite otherwise nearly identical circumstances.3

Nice agate nodules and agate-lined geodes can sell for a lot of money. Collectors often pay hundreds or thousands of dollars for excellent specimens that have been cut and polished. Gem cutters sometimes pay hundreds of dollars per pound for agate that is especially colorful or marked with interesting designs. They cut these into cabochons for use in jewelry or for gemstone collectors. With that in mind, it is easy to understand why people who own land where valuable agates can be found do not want "agate pickers" on their property. Image copyright iStockphoto / WojciechMT.

What Does "Legal" Mean?

Additionally, when the question of an activity's "legality" and whether that activity is "legal" is raised, it sometimes creates confusion. Colloquially, when people ask whether something is "legal" or "illegal," in most cases, they are really asking "can I do it without getting into trouble?" It's certainly a fair question, but it's a question with two possible levels of meaning. The confusion results primarily from the criminal-civil dichotomy in the American legal system.4 In a criminal context, whether an activity is "legal" means that someone cannot be subjected to criminal prosecution, the guilty penalty for which is typically a fine or imprisonment (and, possibly, some form of restitution), for engaging in that activity. Criminal cases are entirely about the "guilt" or "innocence" of a defendant. Criminal activity results from the violation of criminal laws (e.g., speeding prohibitions), which are generally pursued by government law enforcement agencies. In a sense then, committing a crime is a public offense. In a civil context, whether an activity is "legal" means that someone cannot be sued by another person, the liability for which is typically a judgment for monetary damages or injunctive relief, for engaging in that activity. Civil cases are not really about the "guilt" or "innocence" of a defendant. Civil liability results from the violation of another person's individual rights (e.g., property rights), which are generally pursued in civil court by that person on his or her own behalf by filing a lawsuit. In a sense then, committing a civil violation is a private offense. Criminal violations and civil liability are independent, but can overlap and oftentimes result from the same activities. Thus, sometimes an activity that is a criminal offense can also create civil liability. Other times, an activity that is a criminal offense will create no civil liability. Likewise, sometimes an activity that creates civil liability will not constitute a criminal offense. For example, let's say that Max takes Guy's Lamborghini Gallardo without permission and damages it. Max may be guilty of committing the criminal offense of theft for which he may be given a fine or, more likely, imprisoned. Max may also have civil liability to Guy for the same conduct under a civil theory of conversion and negligence. To say that an activity is "legal" could mean either 1) that it is not a criminal offense; or 2) that it would create no civil liability. Or it could mean both. Accordingly, when considering whether an activity like rock, mineral, or fossil collecting is "legal," the question should be considered and evaluated in both the criminal and civil contexts.

This looks like one of the world's most innocent activities, but if the rocks are removed from certain types of property it could be a violation of regulation, law, or personal property rights. The most severe consquence will likely be a warning, but, one never knows what can happen. Image copyright iStockphoto / emholk.

But Will I Get Caught?

Rock, mineral, and fossil collectors may also wrestle with the distinction between legal and practical realities when considering collecting activities. As is often the case, legal principles do not always match up with practical circumstances, and someone who does something illegal may not always be caught, let alone prosecuted or sued. Simply put, specimen collectors may find themselves in situations where they could engage in illegal conduct seemingly without fear of discovery or negative repercussions. Regardless, it would be irresponsible to condone illegal or unethical behavior. Published codes of ethics for rock collecting and rockhounding are intended to serve as guidelines for making moral and ethical choices associated with the hobby; however, ultimately, adherence to the legal realities of collecting oftentimes becomes a matter of one's personal character. Additionally, morality and ethics aside, the risk of being caught and prosecuted or sued always exists for criminal and civil offenders even when that risk is unexpected or unanticipated. Coincidences do happen.

This article is directed toward individual rock, mineral, and fossil collecting hobbyists. Accordingly, the legal principles explained in this article are applicable primarily to persons, not companies or other legal entities. While criminal and civil laws are oftentimes also applied to companies and other legal entities, in most instances, those organizations would likely have people engaging in collecting on their behalf for commercial purposes, which is, itself, relevant to the legality of certain rock, mineral, or fossil collecting activities.

The Importance of Rock, Mineral, or Fossil Ownership and Possession

The most important factor in assessing the legality of rock, mineral, and fossil collecting activities is the legal ownership or possession of the specimens being collected; the question of the ownership and possession of those specimens is the starting point for further legal analysis. Ownership of rocks, minerals, and fossils entails complete control of those specimens in the most extensive sense, still subject to applicable laws, however. Rights of possession of rocks, minerals, or fossils, while legally distinct from ownership, entails less control in a more limited sense, once again, still subject to applicable laws. Ownership typically includes the right of possession, while the right of possession often does not indicate ownership.5 For example, a person may have ownership of a piece of real estate, but may have leased that real estate to a company. In that situation, the company generally has the right of possession to the real estate, although the person still retains ownership of the real estate. Both ownership and rights of possession are relevant to rock, mineral, or fossil collecting as crucial for determining what rules are applicable and what permissions are needed for rock, mineral, or fossil collecting.

| This Stuff Really Happens! |

|

Italian Police Catch Tourist Stealing Stones From the Ancient City of Pompeii

BLM officer detains family 5 hours for picking up rocks Canadian teen jailed for taking rock from Parthenon in Greece |

Ownership or Possession of Rocks, Mineral, and Fossils

Contrary to a common perception, all rocks, minerals, and fossils are treated as being owned or possessed by some person or entity in the American legal system; there are no specimens that are wholly "unowned" as a legal concept. Even in cases where no specific person or organization has ownership of rocks, minerals, or fossils or the property on which rocks, minerals, or fossils are located, federal, state, or local governments have what constitutes default ownership or possession of those specimens or that property.6 In the majority of instances, the ownership of particular specimens located on the surface follows the ownership of the land upon which those specimens are located so that the person who owns the land also owns those surface specimens.7 In certain situations, however, this default rule is not applicable due to legal relationships in which the right of possession for those surface specimens is transferred to another person or organization. For example, the owner of land may lease or place a conservation easement on that land transferring the right to possess and, therefore, control surface specimens to a non-profit organization. The non-profit organization would have the legal right to those surface specimens. Likewise, when specimens are not located on the surface of land or are comprised of specific, recognized minerals or stone, the owner or possessor of a legal interest, oftentimes referred to as a mineral or stone interest, owns those specimens. By way of example, the owner of land may transfer the mineral and stone interest associated with the land to a limestone quarrying company. The limestone quarrying company would have the legal right to subsurface rocks and, depending on the specific language and interpretation of the transfer documents, the limestone rocks located on the surface.

Collecting Publications: Many state geological surveys in the United States have published collecting guides for fossils, rocks, and minerals. These guides often provided the locations of sites where nice specimens have been found in the past. The sites were often on private property and caused problems for some landowners. As a result, some surveys stopped distributing these publications.

The Necessity of Permission or Consent

When considering the legalities of rock, mineral, or fossil collecting, the foremost principle is that a collector cannot legally take rocks, minerals, or fossils without the permission or consent of whoever has a legal right to those rocks, mineral, or fossils. Admittedly, this framework may seem overly technical and complicated when applied to small, loose, easily-taken stones located on the surface of land. Surely, it might appear, there would be no real harm or illegality in taking a few loose stones for personal use from unused, natural land when out on a brief hike. Nonetheless, this framework is the one in which questions of the legality of collecting even small, loose stones would be answered if such legal questions are raised. In every state taking the property of another, which would ostensibly extend even to rocks and other specimens, could violate criminal theft or larceny laws and serve as the basis for a lawsuit for civil liability against the person collecting the rocks from the land of another without permission. Many criminal laws are written in terms of wrongfully taking or exercising control or possession over property belonging to someone else.8 With such broad language, it becomes easy to see how property owners and law enforcement officials could interpret and apply these criminal laws to rocks and other specimens located on private property. One man from Michigan, who was arrested for taking stones placed in a road median for his garden and ended up paying in excess of $1,000.00 in fines and fees, provides one such example. Another Michigan man who took landscaping rocks from restaurant property was similarly charged with larceny and fined. The three people charged with stealing rocks from a levee in Arkansas are yet another example. There is no shortage of instances where people have been criminally or civilly charged for taking rocks and other specimens from the property of others.

| Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Determining Rock, Mineral, or Fossil Ownership and Possession Part 3: Additional Conditions, Limitations, and Prohibitions on Rock Collecting |

|

Timothy J. Witt is an attorney with the firm of Watson Mundorff, LLP. He can be reached by email at  This article does not provide legal advice and does not create an attorney-client relationship. If you need legal advice, please contact an attorney directly. |

| Footnotes |

|

^ 1 There are numerous instances throughout the United States and around the world where individuals have been criminally charged or civilly sued for trespassing on property and taking rock or other natural specimens.

^ 2 Indeed, while laws in the United States generally do not specifically address rocks and similar specimens, laws may be more specific in other areas. For example, New South Wales in Australia has a theft statute that expressly and specifically applies to rocks. See Crimes Act of 1900 - Section 521A: "Whosoever steals: (a) any rock or rocks, (b) any stone or stones, or (c) any gravel, soil, sand or clay, that is or are in, on or under, or forms or form part of any land shall, on conviction by the Local Court, be liable to imprisonment for 6 months, or to pay a fine of 5 penalty units, or both." Indeed, theft of rocks and specimens, particularly from historically or culturally significant areas, has become a big problem all across the globe. In one instance from the recent past, one American man was charged with theft and faced up to twelve years in prison in Turkey for taking rocks from a beach he had visited in that country. ^ 3 The applicability of and distinctions between federal, state, and local laws is always important, but can be even more significant in certain parts of the country. For example, in the eastern portion of the United States, the federal government manages a relatively smaller total area and substantial deference is given to state and local governments on non-federal lands. In the western portion of the United States, however, large areas are governed by federal agencies where state and local laws are largely preempted. Such distinctions merely serve to underscore the importance of knowing the laws that apply to a particular area or even property. ^ 4 The distinction between civil and criminal proceedings is an important one that oftentimes gets blurred. Generally, governmental bodies prosecute criminal violations and assess criminal penalties, while civil actions involve both public and private parties and are based on damages, injuries, or other losses or rights violations. Adding some complexity to this distinction, however, is the fact that governmental bodies often pursue civil penalties in ways similar to criminal penalties (e.g., Federal Trade Commission pursuing civil penalties under consumer protection statutes; Bureau of Land Management pursuing civil penalties for onshore oil and gas regulation violations; Environmental Protection Agency pursuing civil penalties for environmental law violations; the Department of Labor pursuing civil penalties for employment and safety laws). ^ 5 Sylvia L. Harrison in her article discussing mineral estates on public lands provides an excellent explanation of the various types of interests that an owner might have in mineral interests or estates: "1. Possessory Interests. Fee simple interests: At English common law, and under American assumptions founded on English common law, the right to minerals has long been recognized as a corporeal interest in land that can pass by inheritance or grant. With the exception of sovereign claims, at common law the owner of the surface presumably owns fee simple title to the minerals. The fee owner, however, can convey the mineral estate separately from the surface, and confusion frequently arises not only as to the scope of the mineral interest conveyed, but also as to its nature. Mineral leases: Mineral leases are among the most common form of mineral conveyance today. Technically, a lease is a possessory interest, but in the case of mineral leases, "possessory rights" are often severely circumscribed by the terms of the lease. Ambiguous lease instruments may be construed as creating profits, and vice versa. The argument generally arises in disputes over the extent of the mineral holder's rights to use the surface estate. 2. Quasi-Possessory Interests. Easements and profits: Under Roman Law, superimposed freehold interests were prohibited, and therefore rights to work minerals or quarry stone from another's property were in the nature of quasi-possessory interests analogous to easements and profits rather than separate fee interests. Although the extent of Roman influence on modern mineral conveyances is open to speculation, quasi-possessory interests in mineral rights are common today. In modern conveyances, easements are employed primarily to grant access or exploration rights to minerals, whereas "profits" (profits a prendre) grant the right both to enter upon and to extract a mineral product from another's land. 3. Non-Possessory Rights. Royalties: A royalty interest is an interest in the production or revenues from production of oil, gas or other minerals from a given mineral fee estate. Royalties are commonly conveyed in conjunction with a lease of the mineral interest, but do not necessarily relate to any underlying lease or production contract. The grant or reservation of a royalty simply entitles the holder to a portion of production, but conveys none of the "usual attributes of ownership, such as the right to possess, lease or otherwise control the minerals." Licenses: The right to remove minerals, particularly sand and gravel, from another's land is sometimes granted through a "license." A license is commonly defined as "permission to do an act or series of acts on another's land, that absent authorization, would constitute trespass." Licenses differ from easements and profits in that they are generally considered to be revocable by the landowner at will and do not rise to the level of an "interest" in land." Harrison, Sylvia L., "Disposition of the Mineral Estate on United States Public Lands: A Historical Perspective," 10 Pub. Land L. Rev. 131 (1989). ^ 6 The question of the ownership, possession, or other rights to rocks and specimens oftentimes becomes a question of state law and may be somewhat different from state to state. See Black Hills Inst. of Geological Research v. S. Dakota Sch. of Mines & Tech., 12 F.3d 737, 742 (8th Cir. 1993) (concluding that fossils constitute "land" under South Dakota law). ^ 7 In some instances, the case for ownership of rocks is particularly strong. While a property owner is generally recognized as the owner of rocks naturally located on his or her property, the property owner's rights to rocks that are specifically placed on the property (e.g., rocks for landscaping, decorative, recreational, or support purposes) becomes even stronger and clearer. One interesting hypothetical that remains, however, is the ownership of rocks recently and naturally placed on one's property perhaps as the result of an avalanche or rockslide. In that case, it may, perhaps, be an open question as to the ownership of those rocks. ^ 8 Alaska: (theft generally; theft in the fourth degree); Arizona (theft generally); Arkansas (theft generally); California (theft generally; petty theft); Colorado (theft generally); Florida (theft generally); Hawaii (theft generally); Idaho (theft generally); Kentucky (theft generally); Maine (theft generally); Michigan (theft generally); Minnesota (theft generally); Montana (theft generally); Nevada (theft generally); New Hampshire (theft generally); New Mexico (theft generally); New York (theft generally); North Dakota (theft generally); Ohio (theft generally); Oregon (theft generally); Pennsylvania (theft generally); South Dakota (theft generally); Texas (theft generally); Utah (theft generally); Washington (theft generally); Wyoming (theft generally). |

| More Minerals |

|

Herkimer Diamonds |

|

The Acid Test |

|

Tumbled Stones |

|

Zircon |

|

Fool*s Gold |

|

Kyanite |

|

Rock Tumblers |

|

Rhodochrosite |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|