Home » Meteorites » Meteorite Hunting

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

METEORITE HUNTING: THE SEARCH FOR SPACE ROCKS

With a special report on the West, Texas fireball

The seventh in a series of articles by Geoffrey Notkin, Aerolite Meteorites

West, Texas meteorite: My first find during the West, Texas fireball chase. This 18.8-gram L6 chondrite broke up in flight and landed with its fusion crust facing down. The light colored interior was extremely difficult to see against the surrounding straw and I nearly missed it completely. Although we searched the surrounding area thoroughly, we were not able to recover any other pieces of this stone, suggesting that it fragmented at a fairly high altitude, while the remnants landed elsewhere. Preliminary analysis indicates that the interior of some stones is brecciated and may contain rare halite crystals. Photograph by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

My long-time friend and expedition partner, Steve Arnold, is fond of saying that meteorites are the ultimate collectible. They are rare and exotic, of great scientific and historic interest, and they are the only part of outer space that most of us will ever hold in our hands. Many of them are strikingly beautiful as well.

Professional Meteorite Hunters

To me, the only thing better than owning a meteorite is finding one myself, and that can be a daunting task. Every few days I receive an enthusiastic email from someone who has seen one of our television shows or read one of my meteorite hunting expedition articles and wants to become a meteorite hunter. One eager young man who had yet to find his first meteorite wrote to me for advice. He was seriously considering quitting his day job, upon which his wife and two children were dependent, and starting a new career searching for space rocks. I suggested that he go on a few weekend trips first, see if he could find one or two meteorites, determine what kind of financial return they might bring, and then decide if he still wanted to pursue such a bold idea. I didn't say that to discourage him. Rather, I encouraged him to go out and try, but meteorites are so difficult to find that only the most skilled and determined (or lucky) hunters can earn a living by scouring our planet's surface for extraterrestrial visitors.

I never heard from the young man again, so I assume he went out a couple of times, came home unsuccessful, and gave up. I can certainly sympathize. There are plenty of times when I have returned to my tent after ten hours of hiking through fields or deserts with nothing to show for it but sunburn and insect bites. A successful meteorite hunter is resourceful, observant, with plenty of stamina and endurance, is willing to research and experiment and, above all, has great patience.

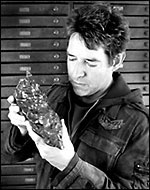

Meteorite hunting in West, Texas: The author (near right in black jacket) and Steve Arnold (far right) discuss how best to maximize their group's time in the West, Texas strewnfield. Four team members can be seen gridding the field in the background. With hundreds of acres to cover, the entire team worked long days to recover as many specimens as possible before spring planting began. Photograph by Suzanne Morrison, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Logging a find: The author logging the exact location of a new find in the strewnfield. Recording find information is important for strewnfield mapping and may help specialists estimate the size of the original meteoroid. Note the small, fusion crusted stone slightly below the yellow GPS unit. Photograph by Steve Arnold, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

How To Find Meteorites

1. Hunting in Known Strewnfields

It may seem fairly obvious, but it is still worth saying: the easiest way to find a meteorite is to go where they have been found before. A strewnfield is a zone where multiple meteorites from the same fall have been recovered. There are many strewnfields around the world, and several here in the United States. One of the best known is Holbrook in northern Arizona. On the evening of July 19, 1912 thousands of stone meteorites rained down outside the small railroad town. Most were about the size of a pea, and upon hearing them hit a tin roof, one eyewitness said they sounded like hailstones. Stones are still occasionally found to this day, and I know several people who found their first meteorite at Holbrook.

2. Meteorite Cold Finds

The adventurous hunter may endeavor to make a cold find. This term refers to a brand new meteorite that is discovered where none have been found before. It is a real challenge and I know several meteorite hunters who have been successful hunting in old strewnfields and on fireball chases [see below] but have never made a cold find. The best hunting locations include dry areas with little or no vegetation, and few indigenous rocks. For example: many new meteorites have been discovered in Antarctica and in our planet's hot deserts. Nearly all meteorites contain a great deal of iron, and iron will begin to decay in moist air, so their chances of surviving long enough to be found, increase in a dry environment.

3. Fireball Chasing

A few times each year a large fireball, also known as a bolide, is seen in the skies over our planet. Some are old satellites or rocket fuel tanks burning up, but the most impressive fireballs are caused by cosmic debris entering our atmosphere. Some fireballs are completely consumed; others fragment and send meteorite fragments raining down upon the earth. When such an event occurs meteorite hunters race to the scene, try to determine where pieces landed, and recover them if possible. This exciting and extremely difficult type of venture is known as fireball chasing.

Collecting and bagging a meteorite: A new meteorite find is carefully placed inside an airtight plastic bag. The delicate fusion crust on recently fallen meteorites is easily damaged, and handling the specimens with gloves helps prevent contamination. It is a thrill being the first human to hold a brand new visitor from outer space. Photograph by Steve Arnold, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Hunting The West, Texas Fireball

On the afternoon of February 15, 2009 a television cameraman covering a race in Austin, Texas captured a spectacular fireball on video. Eyewitnesses to the north in McClellan County saw the fireball close up. Many reported hearing loud sonic booms and one homeowner I spoke with reported that the shock waves broke a window in his house. By studying first hand accounts, specialists were able to predict that if meteorites made it to the ground, they may have done so north of Waco - an astonishing 120 miles from the Austin cameraman who filmed the event. When two small fragments were found by a local rancher, near the town of West, Texas, and presented to a researcher from the University of Texas, we knew the game was on. Steve Arnold left his house in Arkansas almost immediately and drove all night to the fall site. I raced to the Tucson airport and met up with him the following day.

Getting samples of a freshly fallen meteorite into the hands of researchers is the first order of business. Meteoriticists are eager to study new falls as quickly as possible, before specimens have been exposed to rain or the oxidizing effect of our atmosphere. Meteorites that are witnessed falls are financially valuable too: they are very desirable to collectors, especially when associated with a spectacular documented fireball.

When Steve and I are on meteorite hunting expeditions we typically employ sophisticated metal detectors and other equipment that has been specially designed for us, or that we have built ourselves. Hunting the West, Texas fireball was an invigorating change for us, and we went as low-tech as one can get. The West meteorite (provisional name) is a stone, described as an L6 ordinary chondrite, and is one of the most abundant meteorite types. Freshly fallen stone meteorites typically exhibit a rich black fusion crust - a thin, black rind formed as the surface literally burned. This crust makes the meteorites appear much darker than ordinary earth rocks, and will stand out starkly against light colored soil. L6s contain a comparatively low amount of iron, and the meteorites we were hunting for would likely be quite small. We needed to cover a lot of ground quickly, so we left our metal detectors in the trucks, put on our hiking boots, and set out across wide Texas fields.

Finding West, Texas meteorites: A long view across one of our hunting sites within the West, Texas strewnfield. Team members walked in a line, covering two or three plowed rows each, straining to pick out small black rocks among the vegetation and terrestrial rocks. Trying to spot small stones in a big field was a task that required a great deal of patience and stamina. Photograph by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Understanding Fireballs

and Meteorite Strewnfields

Steve was the first of our team to find a meteorite, and it was discovered several miles from the location of the first two specimens. By mapping the locations of these finds and using our knowledge of strewnfields, we were able to extrapolate where might be the best places to hunt for new pieces.

A textbook example of a strewnfield has a roughly elliptical shape and could be a few hundred yards in length, or many miles. Some of the world's largest strewnfields, such as Campo del Cielo in Argentina, encompass hundreds of square miles. Fireballs stop burning high up in the air; atmospheric braking causes the incoming debris to slow down as it falls to earth, usually at a few hundred miles per hour. The largest fragments have more mass and inertia which carries them further, while the smallest fragments crash to earth first. In other words, in a typical strewnfield we expect to find a considerable number of small meteorites at one end, and fewer numbers of larger ones at the far end. Meteorite hunters informally describe these as "the small end" and "the big end."

Meteorite hunting: Found one! The rich black fusion crust on this specimen made it visible from about ten feet away, against the light ochre soil. This is a 100% fusion crusted, perfectly oriented individual, and was found only six days after it fell to earth. Note how this stone has partially buried itself in the ground, forming a small impact pit. Photograph by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Mapping The West, Texas Strewnfield

Our next step was to contact local landowners and ask for permission to hunt on their properties. This is important for two reasons: It is illegal to trespass on private land, and in the United States, meteorites belong to the owner of the land (or in some cases the mineral rights to the land) upon which they have fallen. If the fall site is on Federal land, any finds must be reported and turned over to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

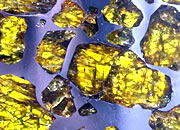

Group of meteorites found in West, Texas: A selection of finds from the West, Texas strewnfield. All of these stone meteorites were part of the February 15, 2009 fireball, witnessed as far away as Austin, Texas. Note the black fusion crust and interesting shapes, caused by melting in our atmosphere. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Finding Meteorites In Texas

|

The West, Texas strewnfield encompasses many different types of ground, including plowed fields, planted fields, grasslands, and forests. It is very difficult to find small, black stones in high grass, or on dark colored earth, so we focused our efforts on expanses of relatively open ground. Spring plowing and seeding were already underway, so the race was on to recover as many stones as possible before the delicate, undisturbed surfaces were pummeled by large tractors. In addition, even a light rain will cause freshly fallen meteorites to begin rusting, so our team worked from dawn to sunset, hiking twelve to fifteen miles each day.

My first find was a partial stone weighing 18.8 grams. I almost missed it, because the broken face was lying up, and the meteorite's interior is bright white - the exact opposite of what our eyes were trained for. Upon turning the stone over, its black fusion crust was immediately apparent.

After a couple of days on the ground, Steve and our colleague Sonny Clary came across a prime hunting location: a large field, only partially covered with the remains of last year's crops. Several small individuals were found within fairly close proximity, telling us we were in the heart of the strewnfield.

Detailed image of one our West, Texas finds. The hair-like features are flow lines, caused as the surface of the meteorite melted and flowed during flight. Note the delicate fissures known as contraction cracks. While burning, the fireball may have reached a temperature in excess of 2,000 degrees F. Once atmospheric braking has slowed the incoming mass and the fire goes out, it is still falling through thin, cold air at high altitude. The rapid temperature change sometimes causes contraction cracks to form in the layer of fusion crust. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Gridding The Strewnfield

In order to fully map that portion of the strewnfield, we invited several of our colleagues to join the hunt. Walking slowly, line abreast and a few feet apart, and using Global Positioning System (GPS) units to record our progress, we laboriously walked back and forth across the immense field until all the ground had been carefully searched. This process took over two days and our team recovered over sixty stones from that one field. We photographed each stone in situ and recorded its precise find location by GPS. Compiling such data helps us further understand the size and shape of the strewnfield. To prevent contamination, specimens were carefully collected while wearing cotton gloves then sealed in airtight bags. Two of our team members found their first-ever meteorite while hunting with us, and the joy and excitement on their faces is something I'll never forget!

The majority of our finds were complete individuals - whole stones that did not break up in the atmosphere, and entirely covered in black fusion crust. A fair number of stones exhibited flow lines, caused by surface melting, and a high degree of orientation. When a meteorite does not tumble during flight, but keeps a fixed orientation towards the surface of our planet, it sometimes melts into a cone or bullet-shaped mass. Orientation is a feature unique to meteorites, and highly oriented specimens are very rare and of great interest to collectors.

Some specimens were found lying, untouched, on the surface. Others had partially buried themselves into the ground, suggesting they fell at high velocity. Several created small impact pits upon hitting the ground, and then bounced, coming to rest a few inches away.

| Meteorwritings Menu |

Earth's Newest Visitors

From Outer Space

Finding a meteorite is a unique and inspiring experience. To be the first person to see, and then hold, a freshly fallen space rock, which was the progeny of a recorded fireball is something rare even for the most adept meteorite hunter. Our West, Texas finds have been photographed and cataloged, and the data we recovered will help meteoriticists further understand the complex mechanics of strewnfields, and may even facilitate speculation regarding the size and speed of the original mass.

It was a privilege to be part of the great Texas meteorite hunt - a never-to-be-forgotten adventure for our team.

Geoff Notkin's Meteorite Book

|

About the Author

|

Geoffrey Notkin is a meteorite hunter, science writer, photographer, and musician. He was born in New York City, raised in London, England, and now makes his home in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. A frequent contributor to science and art magazines, his work has appeared in Reader's Digest, The Village Voice, Wired, Meteorite, Seed, Sky & Telescope, Rock & Gem, Lapidary Journal, Geotimes, New York Press, and numerous other national and international publications. He works regularly in television and has made documentaries for The Discovery Channel, BBC, PBS, History Channel, National Geographic, A&E, and the Travel Channel.

Aerolite Meteorites - WE DIG SPACE ROCKS™

| More Meteorites |

|

What Are Meteorites? |

|

Extraterrestrial Gems |

|

Moldavite |

|

Collecting Meteorites |

|

The Vredefort Crater |

|

Mars Meteorites |

|

Meteorite Identification |

|

Meteorite Types and Classification |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|