Home » Meteorites » Have You Found A Meteorite?

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

HAVE YOU FOUND A SPACE ROCK?

AN INTRODUCTORY GUIDE TO METEORITE IDENTIFICATION

The third in a series of articles by Geoffrey Notkin, Aerolite Meteorites

Meteorwrong: Slag—sometimes called cinder or runoff—is a by-product of metal smelting and usually consists of a conglomerate of metal oxides. Slag is one of the substances most commonly mistaken for meteorites, as it appears burned and melted on the surface and often sticks to a magnet due to its high iron content. It is used in road and railroad building, as ballast, and even in the manufacture of fertilizer. In other words, it is all over the place. Take special note of the vesicles—small holes and cavities created by escaping gases. Vesicles are not found in meteorites, so an experienced eye will immediately identify this as a meteor-wrong. The scale cube pictured is 1 cm. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

How Rare Are Meteorites?

One of my happy tasks as a meteorite hunter is running a website that specializes in my favorite subject. We receive hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, and I try to maintain a fair balance on the site between education, photographs and reports about our expeditions, and commercial sales of meteorites.

Our long-time friend Geoffrey Notkin was kind enough to prepare this video, explaining how the Meteorwritings article series came about and the relationship between Geology.com and Aerolite Meteorites. We greatly appreciate the work that Geoff and his staff put into writing the articles, taking the photos, and creating the banner that you see at the top of this page. It is an honor to have the writings of one of the world's most prominent meteorite experts on Geology.com.

One of the most frequently visited sections of the site is a detailed guide to meteorite identification. As a result of that guide we receive, almost daily, inquiries by letter and email from hopeful individuals who think they may have found a rock from outer space.

Meteorites are among the rarest materials that exist on our planet - far less common than gold, diamonds, or even emeralds. So, the chances of discovering a new example are slim-even for those of us who make their living hunting for, and studying, meteorites. I do spend a significant amount of time each year assisting people who think they may have found the real thing, but the odds are against it. Out of the many hundreds of suspected space rocks sent to us for testing, far less than one percent turn out to be genuine visitors from outer space.

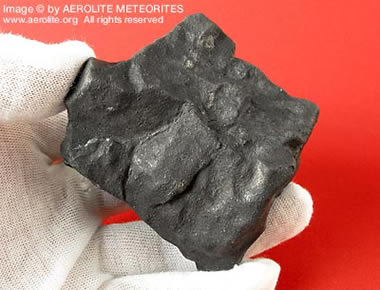

Stone meteorite with fusion crust: This 307.1-gram stone meteorite fell as part of a shower on October 16, 2006 in Mauretania. It is an ordinary chondrite (H5) and an excellent example of a complete fusion crusted stone. This specimen was picked up immediately after the fall. Note the very fresh, rich black fusion crust which is reminiscent of a charcoal briquette. Fusion crust is thin and fragile and will weather away over time, so a recently fallen stone will exhibit a dark black crust with no weathering or rust stains. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

What Are Meteor-Wrongs?

A specimen that is thought to be a meteorite, but turns out instead to be a common earth rock is affectionately and humorously dubbed a meteor-wrong. The surface of our planet is rich in terrestrial iron oxides such as magnetite and hematite (many of which will stick to a magnet), dark black rocks such as basalt, and many different types of man-made metallic by-products such as runoff (slag) from old smelters, and castoff iron implements that have corroded over time.

All of these materials are frequently mistaken for meteorites. Identification of a genuine meteorite takes a practiced eye, but there are a number of simple tests that can help hopeful rock hounds determine if they have stumbled across a rare space rock, or just a common earthbound stone.

Visual Identification of Meteor-Wrongs

Meteorites tend to look different from the ordinary terrestrial rocks around them. They do not contain the common earth mineral quartz, and in general do not contain vesicles. When gas escapes from cooling molten material, it creates small pinprick holes or cavities in a rock's surface. The volcanic rock pumice, often used in skin care for the removal of callouses, contains vesicles which is one of the reasons it is very light in weight. If a suspected meteorite looks like a sponge, with lots of tiny holes, it is probably volcanic rock or slag of earthly origin.

Meteorite Identification:

The Magnet Test

Meteorites are divided into three basic groups: irons, stones, and stony-irons. Practically all meteorites contain a significant amount of extraterrestrial iron and nickel, so the first step in identifying a possible meteorite is the magnet test. Iron and stony-iron meteorites are rich in iron, and will stick to a powerful magnet so strongly that it can be difficult to separate them! Stone meteorites also, for the most part, have a high iron content and a good magnet will happily adhere to them.

Many earth rocks will also attract a magnet, so this is not a definitive test, but it's a good step in the right direction. Lunar and Martian meteorites, and most achondrites (stone meteorites without chondrules) contain little or no iron and even a powerful magnet will generally have no effect on them. However, these meteorite types are so extremely rare that, as a general rule, we discount specimens that will not adhere to a magnet.

Meteorite Identification:

Weight and Density

Iron is heavy and most meteorites feel much heavier in the hand than an ordinary earth rock should. A softball-sized iron meteorite will likely weigh five or six pounds, making it seem unnaturally dense. Imagine holding a steel ball bearing as big as a grapefruit and you'll get the idea.

| More About Meteorite Identification |

| If you would like to learn more about meteorite identification, and discover how to perform some other simple tests at home, please visit The Aerolite Guide to Meteorite Identification. Meteorites are very valuable both to the scientific community and to enthusiastic collectors. So, if you think one landed in your backyard, be sure to get it checked out! |

Visual Identification: Fusion Crust

When a meteoroid (a potential meteorite) streaks through our atmosphere, tremendous heat is generated by atmospheric pressure. The surface of the rock melts and the air around it incandesces. As a result of this brief but intense heating, the surface burns and forms a thin, dark rind called fusion crust.

Meteorites literally began to burn up in our atmosphere, so they tend to appear darker than the terrestrial rocks around them. Desert varnish forms on the surface of some earth rocks, particularly in arid areas, and can easily be mistaken for fusion crust by an untrained eye. True fusion crust does not occur on earth rocks. It is delicate and will weather away over time, but a freshly fallen meteorite will exhibit a rich black crust, much like a charcoal briquette.

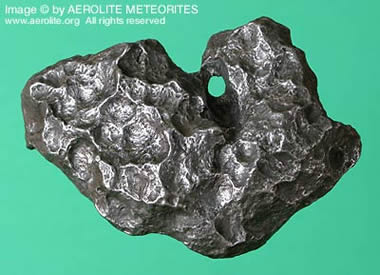

Iron meteorite - Campo del Cielo: This beautiful 654.9-gram Campo del Cielo iron meteorite was found in Chaco Province, Argentina. It is one of the world's oldest-known meteorites and was first discovered by the Spanish in 1576. This example displays excellent regmaglypts (thumbprints), as well as a rare natural hole. This specimen is also oriented. Its leading edge (pictured) is dome-shaped and heavily thumbprinted. The trailing edge is smooth and slightly concave. This specimen measures 114 by 78 mm. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Visual Identification: Regmaglypts

Regmaglypts, popularly known as thumbprints, are oval depressions-often about the size of a peanut-found on the surface of many meteorites. These indentations look much like the marks a sculptor might make with his fingers on a wet lump of clay, hence their name. Regmaglypts are created as the meteorite's outer layer melts during flight and they are another feature unique to meteorites.

Iron meteorite with flow lines: This close-up image of the main mass of the Bruno iron meteorite (found near Bruno, Saskatchewan, 1931) shows a delicate and intricate pattern of flow lines, created as the surface of the meteorite literally melted and flowed. Flow lines may be found on the surface of irons, stones, and stony-irons but, like fusion crust, they are fragile and may disappear over time, due to the processes of terrestrial erosion. Actual size of area pictured is approximately 10 cm across. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Visual Identification: Flow Lines

As our typical meteorite burns through the atmosphere, its surface may melt and flow in tiny rivulets known as flow lines. These patterns formed by flow lines can be minute, often thinner than a strand of human hair, and they are one of the most unique and intriguing surface characteristics of meteorites.

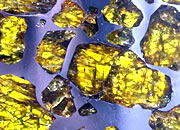

Chondrite meteorite: A prepared end section of the ordinary chondrite Northwest Africa 869 (L4-6, found Tindouf, Algeria, 2000) displays a wealth of colorful grain-like chondrules and multiple tiny flakes of extraterrestrial nickel-iron. The specimen pictured weighs 38.3 grams and measures 60 by 33 mm. Chondrites are the most abundant meteorite group and take their name from the ancient chondrules they contain. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Visual Identification:

Chondrules and Metal Flakes

Stone meteorites known as chondrites are the most abundant meteorite type. They are composed largely of chondrules, which are miniscule, grain-like spheroids, often of differing colors.

Chondrules are believed to have formed in the solar disk before the planets in our solar system and are not present in earth rocks. Chondrites are also typically rich in metal flakes of iron-nickel, and shiny blobs of this extraterrestrial alloy are often visible on their surfaces, though you may need a hand lens to see them.

A simple test involves removing a small corner of a suspected stone meteorite with a file or bench grinder and examining the exposed face with a loupe. If the interior displays metal flakes and small, round, colorful inclusions, it may well be a stone meteorite. Please see the accompanying photographs for illustrations of these and other features.

Meteorite analysis laboratory: A partial view of the impressive Ion Beams for Analysis of Materials (IBeAM) facility at Arizona State University in Tempe. This remarkable device allows specialists to study the composition of suspected meteorites (and other materials) in great detail. A small specimen is placed in a chamber and then bombarded by accelerated ions. The results appear on an adjacent computer screen in seconds. The author gratefully acknowledges the generous assistance of the ASU IBeAM Facility during the preparation of this article. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

| Meteorwritings Menu |

Lab Testing of Meteorites: Nickel

Nickel is rare on earth but almost always present in meteorites. If a suspected meteorite passes the magnet test and looks promising following a visual inspection we may elect to conduct a test for nickel.

|

Assay labs can perform an analysis of the nickel content for a few dollars, but it is necessary to cut off a modest sample in order to perform such a test. Some labs and universities with meteoritics departments can perform more sophisticated tests without damaging a specimen.

I recently had the pleasure of visiting the Ion Beams for Analysis of Materials (IBeAM) facility at Arizona State University in Tempe. ASU curates the world's largest university-based meteorite collection and they also utilize some of the most hi-tech meteorite identification equipment available today.

The IBeAM uses accelerated ions to determine, with great accuracy, the composition of samples. In simple terms, that means we can discover the chemical makeup of a specimen without cutting it up on a diamond saw. The results appear on a computer screen within a few seconds, and a compositional analysis showing somewhere between three and ten percent nickel will almost certainly indicate an authentic meteorite.

Geoff Notkin's Meteorite Book

|

About the Author

|

Geoffrey Notkin is a meteorite hunter, science writer, photographer, and musician. He was born in New York City, raised in London, England, and now makes his home in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. A frequent contributor to science and art magazines, his work has appeared in Reader's Digest, The Village Voice, Wired, Meteorite, Seed, Sky & Telescope, Rock & Gem, Lapidary Journal, Geotimes, New York Press, and numerous other national and international publications. He works regularly in television and has made documentaries for The Discovery Channel, BBC, PBS, History Channel, National Geographic, A&E, and the Travel Channel.

Aerolite Meteorites - WE DIG SPACE ROCKS™

| More Meteorites |

|

What Are Meteorites? |

|

Extraterrestrial Gems |

|

Gifts That Rock |

|

Collecting Meteorites |

|

Moldavite |

|

The Vredefort Crater |

|

Mars Meteorites |

|

Meteorite Identification |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|