Home » Meteorites » Stone Meteorites

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

STONE METEORITES

THE CRUST OF OTHER WORLDS

The eighth in a series of articles by Geoffrey Notkin, Aerolite Meteorites

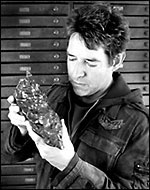

Allende: A complete individual of the Allende carbonaceous chondrite, which fell in Mexico in 1969. Note the black fusion crust that overlies a mottled grey and white interior. The spiderweb pattern within the fusion crust is made up of contraction cracks, caused by rapid cooling in cold air at high altitude once the stone stopped burning in the atmosphere. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

In the second episode of Meteorwritings, "Meteorite Types and Classification," we presented an overview of the three main families of space rocks: irons, stones, and stony-irons. This month we take an in-depth look at the largest of those groups, the stones, discuss where they come from, how they were formed, and will look at some important examples.

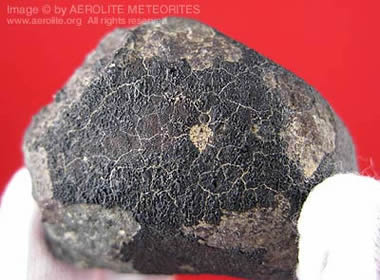

Camel Donga is a rare type of achondrite known as a eucrite. In compositional terms eucrites are quite similar to basalts found on Earth, and they may have originated on the large asteroid Vesta. Note the exceptionally glossy black fusion crust, which is typical of eucrites. Unlike most meteorites, eucrites are not rich in iron, and will not adhere to a magnet. This small, complete individual is only 7.4 grams in weight. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Where Do Stone Meteorites

Come From?

Take a pensive look outside the window of your car while you are driving, or better yet, watch the hills, valleys and plains roll by as you travel on-board a train or airplane. The landscape that reveals itself to us is, obviously, only the surface of our home planet.

In geologic terms it is our planet's crust, which a dictionary might define as "the outermost solid layer of a planet or moon." The outer crust of our planet is very different from other bodies in the Solar System, as it is rich in oxygen and water. Our planet's surface has been shaped and altered by the relentless action of rain, wind, and ice. In addition many of the sedimentary rocks that make up the Earth's crust are rich in fossils—the remains of ancient life forms—but so far no fossil record of life on other planets has been discovered.

With the enormous tectonic plates that make up the Earth's crust moving, causing earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, the ground we stand upon is constantly changing. So, one might use a little artistic license and say that our planet is living, in addition to being unique in the Solar System.

Most meteorites that have fallen upon our planet originated within the Asteroid Belt, which lies between Mars and the gas giant Jupiter. A comparatively small number of meteorites are known to have come to us from two of our closest neighbors-Mars, and our own moon. A few specialists have theorized that some meteorites may even be remnants of comet nuclei.

However, the vast majority of stone meteorites were once part of the crust of asteroids. Cosmic collisions caused some of these wandering space nomads to break up, hurling fragments in different directions. Some of this debris crossed our planet's path, hitting the atmosphere at thousands of miles per hour, burning briefly in the cold, thin air and producing the spectacle we call meteors or shooting stars. Those that survive to land on the surface are known as meteorites.

Gao-Guenie: An attractive example of the ordinary chondrite Gao-Guenie which fell in Burkina Faso in 1960. This stone meteorite was found many years after the fall and it has begun to oxidize, though traces of the original black fusion crust are still evident. This 249-gram complete individual displays faint regmaglypts (thumbprints), which are more commonly seen on iron meteorites. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Chondrites: The Most

Abundant Type of Meteorite

There is nothing commonplace about meteorites. They have come to us from space, can give us clues to the makeup of our neighboring celestial bodies, and can even help us to understand how the Solar System evolved; so the term ordinary chondrite might seem a little misleading.

Ordinary chondrites are the most common type of meteorite, but they are still rarer than platinum or diamonds. Chondrites take their name from the chondrules they contain - small grain-like spheres of varying sizes and colors.

Chondrules are never found in terrestrial rocks and are believed to have formed within the solar nebula disk, billions of years ago, and therefore predate the planets and asteroids that now make up the Solar System. Their exact origin remains something of a mystery. Noted meteoriticist Dr. Rhian Jones of the Institute of Meteoritics in Albuquerque explains:

"Chondrules were heated until they melted and then cooled again very quickly, in just a few hours. Chondrules were described over 100 years ago as 'drops of fiery rain,' by H. Sorby . . . They might have been heated when shock waves passed through the solar nebula, or they might have been heated by sunlight when chondrules were thrown above the disk by strong magnetic fields."

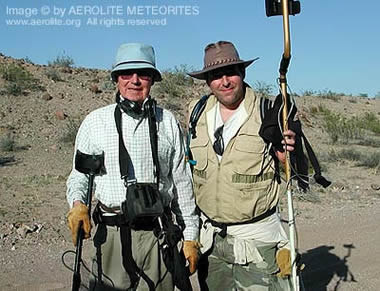

Meteorite hunting in Arizona: The late Professor Jim Kriegh (above left), discoverer of the Gold Basin strewnfield, and the author hunting for stone meteorites with hand-held metal detectors in the Arizona desert. Photograph by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

The Classification of Chondrites

All ordinary chondrites (OCs) contain abundant flecks of the same extraterrestrial nickel-iron that comprises iron meteorites [see Meteorwritings Episode Six - Iron Meteorites]. The metallic content makes OCs feel heavier than earth rocks, and they will easily adhere to a strong magnet. Testing a suspected chondrite with a powerful rare earth magnet is always our first step when hunting for meteorites in the field.

Ordinary chondrites are classified according to the amount of iron they contain, and are divided into three groups: H, L, and LL; with "H" indicating a high iron content and the "L" and "LL" types containing lower amounts of metal. A number, from 1 to 7, indicating the petrologic type, as determined in 1967 by W. Randall Van Schmus and John A. Wood, follows the letters. The number indicates the degree to which chondrules were altered by heat or water on their parent bodies. For example, the H5 classification for Gao-Guenie—a stone meteorite that fell in 1960 in Burkina Faso, Africa—tells us it has a high iron content and is a type 5 chondrite, significantly altered by heat metamorphism.

Juancheng meteorite: The Juancheng meteorite shower of February 15, 1997 was one of the most significant stone meteorite falls in recent history. Over a thousand meteorites fell in Shandong, China. Many were picked up immediately after the fall, including this 290-gram complete stone. Note the fresh black fusion crust and faint regmaglypts. The white areas are chips in the fusion crust, likely caused at the moment of impact, and clearly show the meteorite's light interior. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Petrologic Types: A Brief Summary

- Type 1 and 2 chondrites have been altered by water on their parent body

- Type 3 chondrites show little altering (unaltered chondrules)

- Type 4, 5, and 6 chondrites have been altered to different degrees by the action of heat (thermal metamorphism)

- Type 7 chondrite classification is the subject of some debate but is usually used to describe chondrites with no surviving chondrules

| More About Meteorite Identification |

| If you would like to learn more about meteorite identification, and discover how to perform some other simple tests at home, please visit The Aerolite Guide to Meteorite Identification. Meteorites are very valuable both to the scientific community and to enthusiastic collectors. So, if you think one landed in your backyard, be sure to get it checked out! |

Carbonaceous Chondrites:

Life From The Stars?

Carbonaceous chondrites are also known as C chondrites, and some of them are the oldest matter known. They contain carbon, organic compounds, and sometimes water.

There are several subgroups of C chondrites, including CI, CM, CR, CO, CV, CK, and CH. The second letter typically refers to the first meteorite of that group to be recognized. For example, the "V" in CV chondrites, which contain calcium, aluminum and titanium inclusions, is taken from the Vigarano meteorite that fell in Emilia-Romagna, Italy on January 22, 1910. Some meteoriticists have speculated that water and organic compounds may have first been brought to our planet by C chondrites.

Monze is an L6 ordinary chondrite which fell in southern Zambia on October 5, 1950. This specimen has been cut and polished by a preparator to reveal its interior. Note the abundant shiny flakes of nickel-iron. The small spherical inclusions which look much like orange and yellow grains are chondrules from which the chondrites take their name. The specimen pictured is 86 mm x 62 mm in size and weighs 68 grams. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Other Chondrite Groups

Other subgroups include the rare R chondrites, which are oxidized and high in oxygen content, and the E chondrites, named after the mineral enstatite, which they contain.

West, Texas meteorite: On February 15, 2009 a spectacular daytime fireball was captured on film over central Texas. Pieces fell to earth north of Waco, TX and along with other meteorite hunters I traveled to the fall site. Our team recovered numerous meteorite specimens only days after they had fallen. Here we see a small complete individual with black fusion crust, just as I found it in a field in McLennan County. Classified as an L6 chondrite it has been given the provisional name of West. Learn more about the West, Texas meteorite and fireball here. Photograph by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Differentiated Asteroids and Achondrite Formation

The Glossary of Geological Terms describes a differentiated planet as "one that is chemically zoned because heavy materials have sunk to the center and light materials have accumulated in a crust." That term describes our own planet and also applies to those asteroids that were heated soon after formation. Heating was caused by the decay of radioactive elements, and possibly compounded by asteroidal collisions. Thermal action altered, and in some cases, obliterated chondrules, which is why we do not find chondrites on our own planet. Stony meteorites that do not contain chondrules are known as achondrites and are the product of differentiated bodies. Achondrites contain little or no iron and many are not unlike volcanic rocks found here on Earth.

Wiluna is an H5 chondrite that fell in Western Australia on September 2, 1967. Approximately 500 stones are believed to have landed, most of which were small. This grouping shows seven individuals picked up some years after the fall. Note the prominent contraction cracks on the specimens shown far left and far right. After a few decades in our oxygen-rich atmosphere, the fusion crust has begun to terrestrialize, and is no longer the dark black associated with fresh falls. Most Wiluna specimens went to museum collections in Australia and attractive, complete stones such as these are rarely seen on the collectors' market. Photograph by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Types of Achondrites

|

Eucrites, such as the striking Camel Donga meteorite from Australia, are compositionally similar to terrestrial basalts and are often distinguished by an extremely black and glossy fusion crust. Diogenites are extraterrestrial igneous rocks composed largely of magnesium-rich orthopyroxene. The howardites are a particularly interesting subgroup. They are regolith breccias - a composite usually consisting of fragments from eucrites and diogenites, created by meteorite impacts on asteroids. As such, they are meteorites made up of other meteorites. Angrites (basalts rich in pyroxene), Aubrites (enstatite achondrites), Ureilites (low in calcium, high in olivine and pigeonite), and Brachinites (rich in olivine) and all known lunar and Martian meteorites are also achondrites. Primitive achondrites such as the acapulcoites, lodranites, and winonaites bear little resemblance to each other but show evidence of cooling and recrystallization on differentiated asteroids.

| Meteorwritings Menu |

Some Famous Stone Meteorites

ALLENDE

Location: Chihuahua, Mexico

Witnessed fall: February 8, 1969

Classification: CV3.2 carbonaceous chondrite

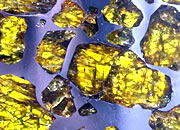

Allende is a fascinating meteorite and highly prized by researchers and collectors alike. It is rich in carbon, typically exhibits well-preserved fusion crust, and also contains microscopic diamonds. Chondrules and calcium-rich inclusions (CAIs) in the Allende meteorite are 4.6 billion years old, making them the oldest known matter in existence on Earth - predating the formation of our own planet and even our Solar System. The late Dr. Elbert King of NASA's Lunar Receiving Lab visited the strewnfield immediately after the fall in 1969 and recovered numerous specimens, many of which he later made available to researchers all over the world. As a result of his work Allende is often described as "the best studied meteorite in history." Dr. King's adventures are recounted in his enjoyable memoir Moon Trip.

GAO-GUENIE

Location: Burkina Faso, Africa

Witnessed fall: March 5, 1960

Classification: H5 chondrite

On the afternoon of March 5, 1960, after three separate detonations, thousands of stones fell in a relatively small strewnfield. Many were recovered at the time, but occasionally specimens are still found today. Originally known as Gao, this stone was renamed in recent years to include the Guenie meteorite, which was at one time thought to be a separate fall. Examples recovered shortly after the meteorite shower exhibit a rich black fusion crust; more recent finds are somewhat oxidized, and have an attractive ochre patina. Gao-Guenie is a favorite of collectors as it is a comparatively inexpensive stone meteorite. Many stones are oval shaped and oddly reminiscent of Idaho potatoes, though the more collectible examples display regmaglypts and orientation.

GOLD BASIN

Location: Mohave County, Arizona

Date of find: 1995

Classification: L4 chondrite

The recovery of the Gold Basin meteorite is an excellent example of how non-academics can make significant contributions to the science of meteoritics. In 1995 an Arizona gold prospector and retired University of Arizona engineering professor, Jim Kriegh, discovered ancient stone meteorites in Mohave County, AZ. His friend Twink Monrad joined him in the hunt and they spent years carefully documenting hundreds of finds, making Gold Basin one of best mapped strewnfields in history. Gold Basin is sometimes described as a fossil meteorite because the stones have been lying where they fell for an estimated 25,000 years. Even though the exterior shows considerable weathering a few specimens retain some remnant fusion crust, and when cut and polished display a beautiful and colorful interior speckled with abundant metal flakes.

Geoff Notkin's Meteorite Book

|

About the Author

|

Geoffrey Notkin is a meteorite hunter, science writer, photographer, and musician. He was born in New York City, raised in London, England, and now makes his home in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. A frequent contributor to science and art magazines, his work has appeared in Reader's Digest, The Village Voice, Wired, Meteorite, Seed, Sky & Telescope, Rock & Gem, Lapidary Journal, Geotimes, New York Press, and numerous other national and international publications. He works regularly in television and has made documentaries for The Discovery Channel, BBC, PBS, History Channel, National Geographic, A&E, and the Travel Channel.

Aerolite Meteorites - WE DIG SPACE ROCKS™

| More Meteorites |

|

What Are Meteorites? |

|

Extraterrestrial Gems |

|

Gifts That Rock |

|

Collecting Meteorites |

|

Moldavite |

|

The Vredefort Crater |

|

Mars Meteorites |

|

Meteorite Identification |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|