Ametrine

A bicolor quartz gemstone consisting of amethyst and citrine

Author: Hobart M. King, PhD, GIA Graduate Gemologist

Ametrine: Beautiful ametrine gemstones. The center stone is a traditional 50/50 split of amethyst and citrine. The stones on the left and right are artistic cuts that allow light entering the stone to pass through purple amethyst and yellow citrine and blend into beautiful shades of orange, magenta, peach, and a range of other colors. Images courtesy of Minerales y Metales del Oriente S.R.L. and Ametrine.com.

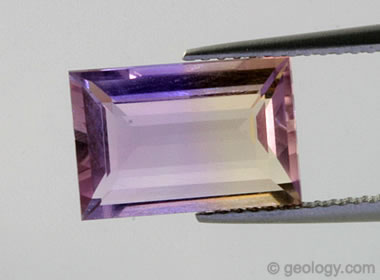

Faceted ametrine: Ametrine has traditionally been faceted in the emerald cut with approximately 1/2 of the stone composed of citrine, 1/2 composed of amethyst, and the dividing line between the color zones perpendicular to the table. This stone has been cut to display the two colors of quartz. It is a 12x8 millimeter emerald-cut ametrine weighing approximately 3.5 carats.

What is Ametrine?

Most people have never heard of ametrine and are very surprised to see purple and yellow in a single transparent gemstone. Ametrine is a rare gemstone with a finite supply that is produced in commercial quantities at only one mine in the world. It is a relative newcomer to the gemstone trade, being available in small quantities for just a few decades.

Ametrine is a variety of bicolor quartz that has zones of amethyst (purple) and citrine (golden yellow) in contact with one another in a single crystal. The words AMEthyst and ciTRINE were combined to yield the name "ametrine," which is widely used in the gemstone trade. This material is known by other less-frequently used names including: "amethyst-citrine," "trystine," "bicolor amethyst," "bicolor quartz," and "bolivianite." The bolivianite name is a response to the material being designated as the national gemstone of Bolivia.

Table of Contents

What is Ametrine? What is Ametrine? Where is Ametrine Produced? Where is Ametrine Produced? What Gives Ametrine Its Color? What Gives Ametrine Its Color? History of Ametrine History of Ametrine Ametrine Gemstones Ametrine Gemstones Synthetic / Treatment-Created "Ametrine" Synthetic / Treatment-Created "Ametrine" Anyone Can Own Ametrine Anyone Can Own Ametrine |

Ametrine mine map: This map shows the geographic location of the Anahi ametrine mine in the Pantanal of eastern Bolivia.

Where is Ametrine Produced?

Ametrine is rarely found in nature. Almost all of the world's commercial ametrine production has been from the Anahi Mine in southeastern Bolivia. The mine has been operated by Minerales y Metales del Oriente S.R.L. since 1989.

The Anahi Mine is in a dolomitic limestone of the Murcielago Group, a sequence of limestones up to 1500 feet thick that dip to the southwest in the area of the mine. Some zones within the Murcielago Group are heavily silicified, causing them to resist weathering and stand up above the surrounding Pantanal lowlands as prominent north-south-trending ridges. The Anahi Mine is in a ridge at a location where the dolomitic limestone is faulted and silicified. [1] Most of the mining activity is done underground, with a small amount of production at the surface. [2]

Hydrothermal activity has facilitated the growth of quartz within fractures and vugs of the dolomitic limestone. The walls of these openings are often covered with a thick layer of massive quartz with euhedral quartz crystals growing inwards towards the center of the cavities. Some of these are crystals of ametrine; many have been etched by later hydrothermal activity.

Ametrine rough: A large piece of very high quality ametrine rough with beautiful richly colored amethyst and citrine in sharp contact with one another. A piece of rough like this could be used to cut stones or carvings. Photo courtesy of Minerales y Metales del Oriente S.R.L. and Ametrine.com.

What Gives Ametrine Its Color?

The colors of amethyst and citrine are produced by iron impurities with different oxidation states within the quartz. Purple is thought to be produced by Fe3+ that is oxidized to Fe4+ by natural radiation emitted by the decay of potassium-40 in nearby rocks. The golden-yellow is thought to be produced by Fe3+. [3]

If a well-formed ametrine crystal is sawn perpendicular to the c-axis, the color zones of amethyst and citrine often form a geometric pattern that radiates outwards from the c-axis like the pieces of a pie. Straight-line contacts separate zones of amethyst from zones of citrine. This pattern is formed by Brazil law twinning in which two quartz crystals of different color are intergrown to form the bicolor gemstone. [4] It is very different from the bicolor zones of a tourmaline crystal which form by sequential crystallization.

Ametrine crystal from the Anahi Mine in Bolivia. Photo courtesy of Minerales y Metales del Oriente S.R.L. and Ametrine.com.

History of Ametrine

According to legend, the Ayoreo Indian tribe of eastern Bolivia knew about the bicolor quartz crystals over 500 years ago. Perhaps the earliest formal documentation of natural quartz crystals with zonal coloring of purple and yellow is in a 1925 issue of American Mineralogist. These were basal sections of quartz crystals with color sectors alternating between purple and yellow. [5]

Reports of a quartz gemstone of mixed purple and yellow color being produced anywhere in the world begin in the 1960s from vague localities in Brazil, Bolivia, and Uruguay. Because the material was not attributed to a specific mine, some people believed it was produced synthetically, produced by treating amethyst, or mined illicitly. [1]

In 1989, changes to Bolivian mining laws allowed gemstone mining in eastern Bolivia, and a company, Minerales y Metales del Oriente S.R.L., obtained exclusive mining rights to a few thousand acres. Their property included a mine location with evidence of a long history of illicit mining. To establish credibility in the gemstone trade, the company invited geologists and gemologists to the mine and allowed them to confirm for themselves that the ametrine and citrine produced there were natural.

Today, their Anahi Mine is the world's only important commercial source of natural ametrine and anahite (a clear variety of quartz with a very light tint of lilac). The mine also produces amethyst, citrine, and bicolor materials that are a combination of amethyst and clear quartz (bicolor amethyst) or citrine and clear quartz (bicolor citrine).

Ametrine faceting rough: Rough ametrine that has been sawn into pieces that are ready for cutting faceted stones. Photograph courtesy of GemFacetingRough.com.

Ametrine Gemstones

A crystal containing both amethyst and citrine in contact with one another can be called "ametrine." These crystals usually contain zones of clear quartz, amethyst, and citrine. When these crystals are cut into pieces that are appropriately sized for faceting gemstones, only a portion of the stones will be ametrine. The remainder will be amethyst, citrine, and clear quartz. This is why the Anahi Mine produces a variety of gem materials and why the amount of ametrine produced is limited.

Byproducts of ametrine mining - amethyst, citrine, and bicolor stones: The Anahi Mine produces ametrine but also amethyst, citrine, bicolor amethyst and bicolor citrine. Samples of these materials are shown above. They are sawn to produce pieces that are ready for faceting. Photograph courtesy of GemFacetingRough.com.

Some of the early people involved in illicit production from the Anahi mine site were intent to produce amethyst and citrine. The novelty of a bicolor gemstone began when some lapidaries, inspired by bicolor tourmaline, began producing emerald-cut stones that were 50% amethyst and 50% citrine with the color boundary oriented perpendicular to the table of the stone. These stones were very attractive and desirable to people who saw them. The bicolor material then became a focus of production.

When Minerales y Metales del Oriente S.R.L. took over the mine, much of the production was being sold as cutting rough and mineral specimens. Since then the owner has worked to diversify revenue by developing the staff and facilities needed to cut the stones, design jewelry, manufacture jewelry, and market the rough, the loose stones, and finished jewelry. Now a large portion of the world's ametrine gemstones are taken from the Earth and delivered to the end consumer through a few related companies located in Bolivia. [2]

New methods of cutting have been developed to make maximum use of a finite ametrine resource. Some stones are still cut in the traditional emerald cut with a 50/50 amethyst/citrine split. Others are cut into "blended ametrine" that has random or planned patches of amethyst and citrine. These stones are cut in orientations that allow light penetrating the stone to pass through zones of purple amethyst and golden-yellow citrine. This can yield beautiful stones with face-up colors that include peach, magenta, and orange.

Physical Properties of Ametrine |

|

| Chemical Classification | Silicate |

| Color | Purple amethyst in contact with golden-yellow citrine |

| Streak | Colorless - harder than a streak plate |

| Luster | Vitreous |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent to transparent |

| Cleavage | None - breaks with conchoidal fracture |

| Mohs Hardness | 7 |

| Specific Gravity | 2.6 to 2.7 |

| Diagnostic Properties | Conchoidal fracture, amethyst and citrine in a single crystal |

| Chemical Composition | SiO2 |

| Crystal System | Trigonal |

| Uses | Gemstone |

Synthetic / Treatment-Created "Ametrine"

Laboratory experiments in 1981 determined that heat and irradiation can be used to convert natural amethyst into a bicolor material that has an appearance similar to natural ametrine. [6] This process is costly to do well and is not known to have produced a significant amount of treatment-created "ametrine."

In 1994 a laboratory in Russia began producing small quantities of synthetic bicolor quartz from alkaline solutions using a hydrothermal process. This synthetic material is being cut, mounted in jewelry and sold in the Russian jewelry market. [7] Some is being exported to other countries and sold as "ametrine." Most of this material has a coloration that an experienced person would immediately recognize as synthetic and not confuse with natural ametrine even though the name is being used.

| More Information About Ametrine |

|

[1] The Anahi Ametrine Mine, Bolivia: Paulo M. Vasconcelos, Hans-Rudolf Wenk, and George R. Rossman; Gems & Gemology, Volume 30, Number 1, Spring 1994, pages 4-23.

[2] Ametrine.com: the official website of Minerales y Metales del Oriente S.R.L., owners of the Anahi Mine, Bolivia. [3] Ametrine: George Rossman, article on the Mineral Spectroscopy Server, California Institute of Technology, 2012. Hosted on the Internet Archive. [4] Quartz (Var: Ametrine): Brian Kosnar, photograph and description published on Mindat.org as photo of the day for February 12, 2010. [5] The Cause of Color in Smoky Quartz and Amethyst by Edward Fuller Holden. Published in American Mineralogist, Volume 9, pages 203-252, 1925. Archived by Google Books. [6] Artificially Induced Color in Amethyst-Citrine Quartz: Kurt Nassau, Gems & Gemology, Volume 17, Number 1, Spring 1981, pages 37-39. [7] Russian Synthetic Ametrine: Vladimir S. Balitsky, Taijin Lu, George R. Rossman, Irina B. Makhina, Anatolii A. Mar'in, James E. Shigley, Shane Elen, and Boris A. Dorogovin; Gems and Gemology, Volume 35, Number 2, Summer 1999, pages 122-134. |

Anyone Can Own Ametrine

If you search online or go to a jewelry store that has a nice selection of colored stone jewelry, you might find a few pieces of ametrine for sale. The price is usually inexpensive when compared to other stones of similar size and beauty - certainly less expensive than bicolor tourmaline. Almost anyone who can afford to purchase jewelry is able to obtain a beautiful item with an ametrine gemstone of reasonable size. They are bargains when the beauty of the stones and the rarity of the material are compared to their price.

| More Gemstones |

|

Tourmaline |

|

Fancy Sapphires |

|

Diamond |

|

Canadian Diamond Mines |

|

Birthstones |

|

Pictures of Opal |

|

Fire Agate |

|

Blue Gemstones |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|