Luster on Quartz and Tourmaline: Quartz and tourmaline usually have a vitreous luster if you examine their crystal faces or conchoidal fracture surfaces. The tourmaline crystals in this photo have an interesting luster. The parallel striations on their surface give them a silky luster - which can be unexpected. Image copyright iStockphoto / halock.

What Is Luster?

Luster is a word used to describe the light-reflecting characteristics of a mineral specimen. The luster of a specimen is usually communicated in a single word. This word describes the general appearance of the specimen's surface in reflected light.

Eleven adjectives are commonly used to describe mineral luster. They are: metallic, submetallic, nonmetallic, vitreous, dull, greasy, pearly, resinous, silky, waxy, and adamantine. These adjectives convey - in a single word - a property that can be important in the identification of a mineral.

The luster of a material can also determine how it will be used in industry. For example, jewelry manufacturers would not be the top consumer of gold if the metal had an unattractive luster. The pearly luster of muscovite makes ground muscovite a common ingredient in cosmetics.

Table of Contents

How to Observe Luster

The luster of a mineral is best observed on a surface that is free of moisture, dirt, tarnish, and abrasion. Geologists in the field usually carry a rock hammer to break rocks so that their true luster and color can be observed. Breakage is usually not necessary when observing the luster of cleaned and cared-for specimens in a laboratory or classroom.

Luster is best observed under direct illumination. That allows the light that strikes the specimen to reflect to the eye of the observer. Proper examination includes moving the specimen (or the light source, or the head of the observer) through a range of angles to observe the full character of the luster.

Types of Luster

The photographs and descriptions on this page illustrate some of the most common lusters observed in minerals.

Silver Metallic Luster in Galena: This photograph shows the silver metallic luster of a nice cubic crystal of galena. The galena crystal is about two inches on a side, and the adjacent white crystals are calcite. Collected from the Sweetwater Mine, Reynolds County, Missouri. Specimen and photo by Arkenstone / www.iRocks.com.

Metallic Luster

Specimens with a metallic luster exhibit the reflectivity and brightness of a metal and are always opaque. The smoother the surface, the brighter their luster, and the higher their reflectivity.

When a beam of incident light is reflected from a perfectly smooth reflective surface, the angle of reflection is equal to the angle of incidence. Smooth surfaces have higher lusters because all of the light that strikes them has an opportunity to be reflected. However, when light strikes a rough surface, much of the light is hitting irregularities in the surface. This light is scattered in many directions. These specimens with an irregular surface will have a lower luster than specimens with a smooth surface.

Most metallic minerals have a color similar to native metals such as gold, silver, or copper. Just because a specimen is highly reflective does not give it a metallic luster. It must also be opaque and exhibit the color of a metal.

Opacity is an important part of a metallic luster. Light enters specimens that are transparent or translucent. When a specimen is opaque, then all of the incident light has an opportunity to be reflected.

Many sulfide and sulfosalt minerals have a metallic luster, such as pyrite, galena, chalcopyrite, and pyrrhotite. Some oxide minerals such as hematite, rutile, magnetite, and cassiterite may exhibit a metallic luster.

Submetallic Luster in Magnetite: A specimen of magnetite (variety: lodestone) exhibiting a submetallic luster. The specimen has attracted numerous tiny particles of iron. This specimen is approximately 10 centimeters across.

Submetallic Luster

Some specimens exhibit a luster that falls short of being called "metallic" or makes the observer doubtful about using that adjective. The word submetallic might be used for these specimens.

These specimens are usually opaque, and they are often black in color. Others have a small grain size, or an irregular or pitted surface that interferes with the reflection of incident light.

Observers should be careful, because tarnish will sometimes mislead them into deciding that a specimen is submetallic rather than metallic or nonmetallic. This is when observations of luster on a freshly broken surface become important.

Hematite, magnetite, graphite, and chromite are examples of minerals that can exhibit a submetallic luster.

Nonmetallic Luster

Most mineral specimens do not exhibit a metallic or submetallic luster. These specimens are said to have a "nonmetallic" luster. There are many varieties of nonmetallic lusters, and the most common are described below.

Note: The name "nonmetallic" applies to the luster of these minerals and has nothing to do with their elemental composition.

Nonmetallic (Vitreous or Glassy) Luster in Apatite: These small greenish yellow crystals of apatite exhibit a vitreous luster. Vitreous means "the appearance of glass". Some people would call this a "glassy" luster, and that would be perfectly correct. The apatite crystals are from Cerro del Mercado, Durango, Mexico, and they are mostly about 8 millimeters in length. Image copyright by Geology.com.

Vitreous Luster

Specimens that have a vitreous luster have a reflective appearance that is similar to glass. This luster is sometimes called "glassy." Many specimens of apatite, beryl, fluorite, and quartz have a vitreous luster. Some specimens of calcite have a vitreous luster on their cleavage surfaces.

Vitreous is the most common type of luster. About 70% of all minerals can exhibit a vitreous luster.

Dull (or Earthy) Luster: A specimen of massive hematite that is non-reflective and would be said to have a dull or earthy luster. It is about four inches across (ten centimeters) and was collected near Antwerp, New York.

Dull Luster

Specimens with a dull luster, sometimes described as an "earthy" luster, are non-reflective. They have a rough, porous, or granular surface that scatters light instead of reflecting light. Kaolinite, limonite, and some specimens of hematite have a dull or earthy luster.

Greasy Luster: A lime-green serpentine cabochon with a wonderful green color and a greasy luster.

Greasy Luster

Specimens with a greasy luster appear to be coated with a thin layer of oil or grease. Some specimens of serpentine, jade, diamond, vesuvianite, and nepheline have a greasy luster.

Pearly (or Nacreous) Luster: Pearls and mother of pearl (the inner layer of some mollusk shells) have a pearly or nacreous luster. Image copyright iStockphoto / barbaraaaa.

Pearly Luster

Specimens with a pearly luster (sometimes called nacreous luster) have a surface with a reflective quality that is similar to a pearl.

This appearance often occurs on cleavage surfaces of transparent to translucent minerals that include some micas, some feldspars, and some carbonate minerals. Examples include muscovite, orthoclase, and calcite.

In these minerals, light enters the mineral and reflects from multiple atomic planes beneath the surface. This can produce an out-of-focus glow of light emerging from shallow depths within the specimen.

Resinous Luster: Pieces of Baltic amber with a yellow to orange color and a resinous luster. Image copyright iStockphoto / IGraDesign.

Resinous Luster

The name resinous refers to the appearance of the resin secreted by conifer trees. Amber, sphalerite, almandine garnet, and some specimens of sulfur exhibit a resinous luster. Specimens with a resinous luster are usually yellow, orange, red, or brown in color.

Silky Luster: A specimen of satin spar gypsum with the reflective fibrous structure that produces a silky luster. Image copyright iStockphoto / Joel Papalini.

Silky Luster

Some mineral specimens are composed of many parallel fibers or parallel crystals that are bound together and reflect light. This produces a luster that is similar to the light reflected from a bundle of parallel silk threads.

The satin spar variety of gypsum is an excellent example of a silky luster. Tiger's-eye, chrysotile (serpentine), tremolite, and ulexite can also exhibit a silky luster.

The tourmaline crystals in the first image at the top of this page have a silky luster produced by parallel striations on prismatic crystals.

Waxy Luster: Three cabochons of various types of serpentine that produce a waxy luster from their polished surfaces. The polish is not bright. Instead it is a soft glow.

Waxy Luster

Materials that have a waxy luster have an appearance that is similar to the surface of a candle, a block of beeswax, or a piece of paraffin. Some specimens of talc, serpentine, rough opal, jade, and the conchoidal fracture surfaces of agate are examples of materials with a waxy luster.

Materials with a waxy luster are usually translucent, and direct light upon them produces a soft waxy glow.

Adamantine Luster: An octahedral diamond crystal in positive relief on the surface of its host rock. Adamantine is the highest level of luster. This diamond crystal is estimated to be approximately 1.5 carats and is from the Udachnaya Mine, Yakutia, Siberia, Russia. Specimen and photo by Arkenstone / www.iRocks.com.

Adamantine Luster

Adamantine is the highest luster observed in minerals. It is a luster that is similar to vitreous, but the adamantine specimens are more reflective. There is no sharp division between a vitreous luster and an adamantine luster. When a specimen has a luster that is difficult to assign to one of these categories, the term subadamantine might be suitable.

Some specimens of diamond, cassiterite, corundum, sphalerite, cerussite, vanadinite, titanite, malachite, rutile, and zircon exhibit an adamantine luster.

Commercial Use of Luster

Many minerals used in commercial products owe their value and popularity at least in part to their luster. The best example is gold. It has a highly reflective metallic luster that resists tarnish. That beautiful luster makes gold the perfect metal for jewelry manufacturing. Today, most of the world's gold is made into jewelry.

Muscovite mica is another mineral that is used commercially because of its luster. Its highly reflective, eye-catching pearly luster, along with its ability to be ground into tiny, flat flakes, makes it the perfect additive in a variety of products. Minute flakes of muscovite bring a glittery appearance to cosmetics, paints, plaster, plastics, tile, pottery glazes, and many other products that people use or see every day.

Luster Is Not Diagnostic

Luster is not a diagnostic property. This means that, for most mineral species, luster can vary from one specimen to another.

For example: hematite can exhibit a metallic luster, a submetallic luster, or a dull luster. A single specimen can exhibit one or more of these lusters.

Because of that, luster cannot be heavily relied upon in mineral identification. It might be considered to be a "hint" that can set a person on the proper route.

A Gemologist's View of Luster

Most geologists, including the author of this article, have not thought as deeply about luster as gemologists. If you open almost any mineralogy textbook to the pages that describe a mineral, the luster is usually given as one or two of the adjectives listed above. For example: submetallic to metallic.

The author completed the coursework for a Graduate Gemologist diploma from the Gemological Institute of America in 2018. While taking his courses, he realized that gemologists put more work into their assessment of luster. They also use luster in gem identification in more ways than geologists use it in mineral identification. A gemologist might report:

a general luster for a mineral (gem) species a general luster for a mineral (gem) species a general luster for a mineral (gem) variety a general luster for a mineral (gem) variety a fracture surface luster a fracture surface luster a cleavage surface luster a cleavage surface luster a polished surface luster a polished surface luster |

In corundum, basal parting planes can exhibit a pearly or submetallic luster. This differs from the vitreous to adamantine luster that might be observed on crystal and fracture faces. A pearly luster on parting planes can indicate that the material might display asterism if cut properly.

Gemologists pay attention to luster because, after color, luster is the most obvious property of an item that will be sold for tens, hundreds, thousands, or millions of dollars.

Here's a problem: You are examining a cabochon (a dome-shaped gem) cut from a material that might be green quartz, chrysoprase (green chalcedony), or dyed quartzite. You know that under a microscope (or a hand lens), the edge where the flat bottom of the cabochon meets the domed top often has at least one tiny chip. You find a chip with a conchoidal shape. How would you be able to tell if the cabochon is cut from green quartz, chrysoprase, or quartzite?

The answer is in the luster of the chip's surface. These three materials have distinctive fracture lusters. Green quartz will be vitreous, chrysoprase will be dull to waxy, and quartzite will be granular.

The problem above was simple. The material could have been one of a large number of gem materials beyond quartz, chalcedony, and quartzite. It might have been jadeite, nephrite, idocrase (vesuvianite), serpentine, amazonite, prasiolite, apatite, heliodor, malachite, tourmaline, diopside, fluorite, a green garnet, gaspeite, emerald, green beryl, kyanite, maw sit sit, moldavite, opal, peridot, aventurine, sphene, spodumene, epidote, variscite, zoisite, or another less-common gem. One look at the luster might eliminate most of the green gems in this list.

Gemologists are also concerned about phenomena. These are things that gem materials do to light beyond a simple luster, such as: adularescence, aventurescence, iridescence, labradorescence, opalescence, play-of-color, and fire. If these are not related to luster, they can be hard to separate from it.

We will conclude with a comment about the luster known as "pearly". There are many kinds of pearls, produced by different types of organisms, who live in different parts of the world, in different types of water. Gemologists who specialize in pearls can teach entire courses on the pearly luster.

| More Minerals |

|

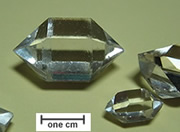

Herkimer Diamonds |

|

The Acid Test |

|

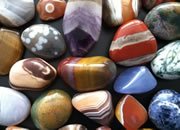

Tumbled Stones |

|

Zircon |

|

Fool*s Gold |

|

Kyanite |

|

Rock Tumblers |

|

Rhodochrosite |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|