Rutile

A source of titanium, a white pigment in paint, a cause of "eyes" and "stars" in gems.

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD

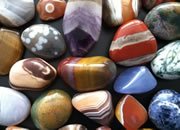

Rutilated Quartz: A tumbled stone of rutilated quartz. Rutile can occur as needle-shaped crystals in minerals such as quartz, corundum, garnet, and andalusite. Image copyright iStockphoto / Coldmoon_photo.

What is Rutile?

Rutile is a titanium oxide mineral with a chemical composition of TiO2. It is found in igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks throughout the world. Rutile also occurs as needle-shaped crystals in other minerals.

Rutile has a high specific gravity and is often concentrated by stream and wave action in "heavy mineral sands" that exist today in both onshore and offshore deposits. Much of the world's rutile production is mined from these sands.

Rutile is used as an ore of titanium, it is crushed into a white powder that is used as a pigment in paints, and it is processed for use in a multitude of products. Networks of needle-shaped rutile crystals produce the "eyes" and "stars" in many gems, such as star ruby and star sapphire.

Heavy Mineral Sand: Shallow digging at Folly Beach, South Carolina, exposes thin layers of heavy mineral sands. These sands are often a source of natural rutile. Photograph by Carleton Bern, United States Geological Survey.

Geologic Occurrence of Rutile

Rutile occurs as an accessory mineral in plutonic igneous rocks such as granite and in deep-source igneous rocks such as peridotite and lamproite. In metamorphic rocks, rutile is a common accessory mineral in gneiss, schist and eclogite. Well-formed crystals of rutile are sometimes found in pegmatite and skarn.

Rutile and a number of other metallic ore minerals are mined together from sedimentary deposits known as "heavy mineral sands". These sediments are derived from the weathering of igneous and metamorphic rocks that contain abundant tiny grains of high-specific-gravity minerals such as rutile, ilmenite, anatase, brookite, leucoxene, perovskite, and titanite (also known as sphene).

As these rocks weather, their more resistant mineral particles are washed into the marine coastal environment where they are sorted and concentrated according to their density by wave and current action. Where conditions are right and heavy minerals are abundant, these sediments can become minable deposits.

Mining Heavy Minerals: Excavators remove heavy mineral sands at the Concord Mine in south-central Virginia. These sands containing up to about 4% heavy minerals are excavated and then processed to remove rutile, ilmenite, leucoxene, and zircon. The sands were weathered and eroded from an anorthosite exposure a short distance away. Photo by the United States Geological Survey.

Rutile Mining

Heavy mineral sands are mined in the shallow marine environment by ships that dredge up sediments, separate out the heavy mineral grains, retain the heavy minerals on-board, and discharge the lighter sediment fraction back to the bottom.

Heavy mineral sands are also found on land in sedimentary deposits that accumulated at times when sea level was much higher than it is today. These sediments are mined, processed to remove the heavy minerals, and returned to a landscape that is reclaimed to its original topography.

Heavy Mineral Sand: A heavy mineral concentrate from an onshore mining operation in Georgia. It is composed of sand-sized grains of mostly rutile, ilmenite and zircon.

Polymorphs and Impurities

Rutile is the most abundant natural form of TiO2. There are numerous polymorphs that include anatase and brookite. Iron (Fe+2) sometimes substitutes for titanium in some specimens of rutile. When this occurs, a valence difference between iron and titanium requires balancing - and that balance is often accomplished by substitution of niobium (Nb+5) and/or tantalum (Ta+5) for another titanium. Substitution of these elements increases the specific gravity of rutile and causes a black color in both the mineral and its streak.

Physical Properties of Rutile |

|

| Chemical Classification | Oxide |

| Color | Red to reddish brown, black, yellow to gold |

| Streak | Red to brown |

| Luster | Adamantine to submetallic |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque, transparent on thin edges |

| Cleavage | Good |

| Mohs Hardness | 6 to 6.5 |

| Specific Gravity | 4.2 to 4.4 |

| Diagnostic Properties | Luster, color, specific gravity, prismatic crystal habit |

| Chemical Composition | Titanium oxide, TiO2 |

| Crystal System | Tetragonal |

| Uses | An ore of titanium, pigments, inert coating on welding rods |

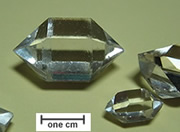

Rutilated Quartz: Two cabochons cut from rutilated quartz. The long prismatic crystals with a golden metallic luster are rutile.

Rutile and Gemology

More than perhaps any other mineral, rutile has an affinity for growing as prism-shaped crystals within other minerals. Long prisms of rutile occur in many different gem minerals. Quartz, corundum (ruby and sapphire), garnet, and andalusite are some of the more familiar.

Sometimes these needles are coarse and clearly visible within the gem, as in many specimens of rutilated quartz. These needles produce attractive and interesting novelty gems when they have a pleasing color and arrangement. See the adjacent photo of rutilated quartz.

The Star of India: This gem is a 563.35-carat star sapphire, cut from rough found in Sri Lanka. It is grayish blue in color and has been cut to display a star on both top and bottom. It is displayed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Wikimedia Commons photo by Daniel Torres, Jr.

In some gems, such as ruby and sapphire, reflections of light from a network of fine rutile crystals within a properly cut cabochon will produce a beautiful "star" of light on the surface of the gem. Gem rubies and gem sapphires with this star are known in the trade as "phenomenal gems", and the phenomenon of the star is known as "asterism". See the adjacent photo of a light blue star sapphire named "The Star of India".

In other gems, one direction of parallel crystals will form a line of light on the surface of the gem known as a "cat's-eye". The phenomenon that produces a cat's-eye is known as "chatoyance", and gems that exhibit that phenomenon are said to be "chatoyant". The best-known gem for its chatoyance is cat's-eye chrysoberyl.

Rutilated Quartz with Cat's-Eye: A cabochon cut from rutilated quartz mined in Brazil. The rutile needles are golden in color and have a texture that is so coarse that many individual needles can clearly be seen. The cabochon is approximately 12 x 16 millimeters in size.

Uses of Rutile

The primary uses of rutile and titanium oxide made from rutile are: manufacturing titanium oxide pigments, manufacturing refractory ceramics, and production of titanium metal. The use of rutile to make pigments touches the lives of almost every person in the United States in many ways almost every day.

When finely crushed and processed to remove impurities, rutile become a bright white powder that serves as an excellent pigment. It is used to make paint by suspending the powder in a liquid. The liquid serves as a carrier in the paint's application, and evaporates to deposit a layer of titanium oxide on the object that was painted. Titanium oxide pigments became very important in the paint industry in 1978, when the United States government banned the use of lead-based pigments in consumer paint products.

Titanium oxide pigments are used to produce white color in plastics, and they are used to make high-brightness paper. Titanium oxide gives these products a color that is resistant to fading. Titanium oxide is also nontoxic and chemically stable. Those properties allow it to be used as a pigment in food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and many consumer products such as toothpaste.

The best way to learn about minerals is to study with a collection of small specimens that you can handle, examine, and observe their properties. Inexpensive mineral collections are available in the Geology.com Store. Image copyright iStockphoto / Anna Usova.

Synthetic Rutile

Rutile has a very high refractive index, a strong dispersion, and an adamantine luster. These are optical properties that can produce a great gemstone, and these properties in rutile rival or exceed those of diamond. Unfortunately, natural rutile rarely has the clarity and color needed to serve as an alternative gem for diamond.

However, synthetic rutile can be made nearly colorless with excellent clarity. When it was first produced in the 1940s and 1950s, it was cut into gems and sold as a diamond simulant named "Titania". It attained a bit of early popularity, but that began to fade once buyers discovered that synthetic rutile suffered from abrasion injuries in just a short time - rutile has a Mohs hardness of 6 compared to diamond's hardness of 10.

| More Minerals |

|

Herkimer Diamonds |

|

The Acid Test |

|

Tumbled Stones |

|

Zircon |

|

Fool*s Gold |

|

Kyanite |

|

Rock Tumblers |

|

Rhodochrosite |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|