Home » Rocks » Metamorphic Rocks » Schist

Schist

A foliated metamorphic rock that contains abundant platy mineral grains.

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD

Muscovite schist: The dominant visible mineral in this schist is muscovite. Its platy grains are aligned in a common orientation, and that allows the rock to be split easily in the direction of the grain orientation. The specimen shown is about two inches (five centimeters) across.

What is Schist?

Schist is a foliated metamorphic rock made up of plate-shaped mineral grains that are large enough to see with an unaided eye. It usually forms on a continental side of a convergent plate boundary where sedimentary rocks, such as shales and mudstones, have been subjected to compressive forces, heat, and chemical activity. This metamorphic environment is intense enough to convert the clay minerals of the sedimentary rocks into platy metamorphic minerals such as muscovite, biotite, and chlorite. To become schist, a shale must be metamorphosed in steps through slate and then through phyllite. If the schist is metamorphosed further, it might become a granular rock known as gneiss.

A rock does not need a specific mineral composition to be called "schist." It only needs to contain enough platy metamorphic minerals in alignment to exhibit distinct foliation. This texture allows the rock to be broken into thin slabs along the alignment direction of the platy mineral grains. This type of breakage is known as schistosity.

In rare cases the platy metamorphic minerals are not derived from the clay minerals of a shale. The platy minerals can be graphite, talc, or hornblende from carbonaceous, basaltic, or other sources.

Chlorite schist: A schist with chlorite as the dominant visible mineral is known as a "chlorite schist." The specimen shown is about two inches (five centimeters) across.

How Does Schist Form?

Schist is a rock that has been exposed to a moderate level of heat and a moderate level of pressure. Let’s trace its formation from its protoliths - the sedimentary rocks from which it forms. These are usually shales or mudstones.

Rock & Mineral Kits: Get a rock, mineral, or fossil kit to learn more about Earth materials. The best way to learn about rocks is to have specimens available for testing and examination.

In the convergent plate boundary environment, heat and chemical activity transform the clay minerals of shales and mudstones into platy mica minerals such as muscovite, biotite, and chlorite. The directed pressure pushes the transforming clay minerals from their random orientations into a common parallel alignment where the long axes of the platy minerals are oriented perpendicular to the direction of the compressive force. This transformation of minerals marks the point in the rock’s history when it is no longer sedimentary but becomes the low-grade metamorphic rock known as "slate."

Slate is has a dull luster, it can be split into thin sheets along the parallel mineral alignments, and the thin sheets will ring when they are dropped onto a hard surface. If the slate is exposed to additional metamorphism, the mica grains in the rock will begin to grow. The grains will elongate in a direction that is perpendicular to the direction of compressive force. This alignment and increase in mica grain size gives the rock a silky luster. At that point the rock can be called a "phyllite." When the platy mineral grains have grown large enough to be seen with the unaided eye, the rock can be called "schist." Additional heat, pressure, and chemical activity might convert the schist into a granular metamorphic rock known as "gneiss."

Garnetiferous schist: This rock is composed of fine-grained muscovite mica with numerous visible grains of red garnet. The specimen shown is about two inches (five centimeters) across.

Emeralds in mica schist: Photograph of emerald crystals in mica schist from the Malyshevskoye Mine, Sverdlovsk Region, Southern Ural, Russia. The large crystal is about 21 millimeters in length. Photograph copyright iStockphoto / Epitavi.

Types of Schist and Their Composition

As explained above, mica minerals such as chlorite, muscovite, and biotite are the characteristic minerals of schist. These were formed through metamorphism of the clay minerals present in the protolith. Other common minerals in schist include quartz and feldspars that are inherited from the protolith. Micas, feldspars, and quartz usually account for most of the minerals present in a schist.

Schists are often named according to the eye-visible minerals of metamorphic origin that are obvious and abundant when the rock is examined. Muscovite schist, biotite schist, and chlorite schist (often called "greenstone") are commonly used names. Other names based upon obvious metamorphic minerals are garnet schist, kyanite schist, staurolite schist, hornblende schist, and graphite schist.

Some names used for schist often consist of three words, such as garnet graphite schist. In these cases the dominant metamorphic mineral’s name is used second, and the less abundant mineral name is used first. Garnet graphite schist is a schist that contains graphite as its dominant mineral, but abundant garnet is visible and present.

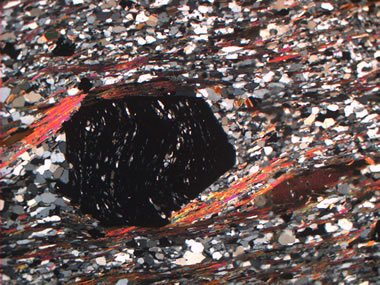

Garnet mica schist in thin section: This is a microscopic view of a garnet grain that has grown in schist. The large black grain is the garnet, the red elongate grains are mica flakes. The black, gray, and white grains are mostly silt or smaller size grains of quartz and feldspar. The garnet has grown by replacing, displacing, and including the mineral grains of the surrounding rock. You can see many of these grains as inclusions within the garnet. From this photo it is easy to understand why clean, gem-quality garnets with no inclusions are very hard to find. It is also hard to understand how garnet can grow into nice euhedral crystals under these conditions. Photo by Jackdann88, displayed here under a Creative Commons license.

Schist As a Construction Material

Schist is not a rock with numerous industrial uses. Its abundant mica grains and its schistosity make it a rock of low physical strength, usually unsuitable for use as a construction aggregate, building stone, or decorative stone. The only exception is for its use as a fill when the physical properties of the material are not critical.

Schist As a Gem Material Host Rock

Schist is often the host rock for a variety of gemstones that form in metamorphic rocks. Gem-quality garnet, kyanite, tanzanite, emerald, andalusite, sphene, sapphire, ruby, scapolite, iolite, chrysoberyl and many other gem materials are found in schist.

Gem materials found in schist are often highly included. This is because their mineral crystals grow within the rock matrix, often including mineral grains of the host rock instead of replacing them or pushing them aside. The best metamorphic host rock for gem materials is usually limestone, which is easily dissolved or replaced when the gem materials are formed.

| More Rocks |

|

Tumbled Stones |

|

Fossils |

|

Geodes |

|

The Rock Used to Make Beer |

|

Topo Maps |

|

Difficult Rocks |

|

Fluorescent Minerals |

|

Sliding Rocks on Racetrack Playa |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|