Home » Landslides » Yosemite Rockfall Hazards

Rockfall Hazards in Yosemite National Park

Much of the spectacular scenery in Yosemite is a product of glacial erosion followed by rockfalls

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD

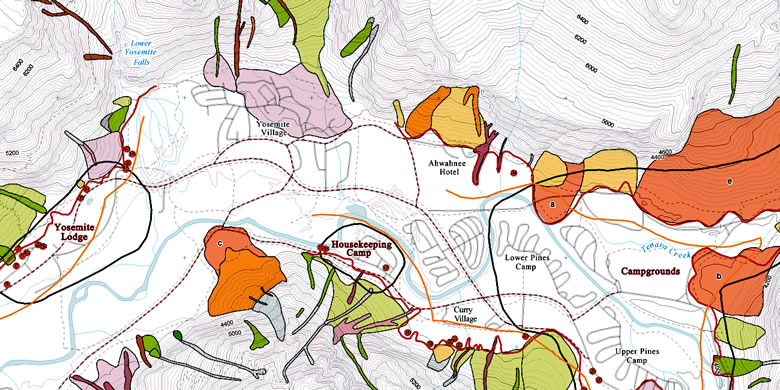

Yosemite rockfall hazards map: This illustration is part of a rockfall hazard map for Yosemite National Park. It shows recent, historic, and prehistoric rockfall and rockslide areas near some of the busiest sites in the park. The National Park Service, United States Geological Survey and others are working to understand the rockfall and rockslide hazards in the park, educate park visitors, and use what they learn to make the park an even safer place to visit. Map from USGS Open-File Report 98-467.

Yosemite hazards: This video by the National Park Service and Yosemite Conservancy demonstrates the rockfall and rockslide hazards in the Yosemite National Park area and explains some of the work being done to learn more about the hazards, educate visitors, and reduce future impact.

Rockfalls and Rockslides - Yosemite Valley

Yosemite Valley is a deep, glacier-carved valley bounded by steep granite cliffs. These steep cliffs produce numerous rockfalls and rockslides every year. These events range in size from individual boulders to massive falls of several million cubic meters. Field work in the park area has documented hundreds of large falls over the past 150 years. Several of these falls have killed people in the valley.

The park receives between three and four million visitors per year. Some of the rockfalls and rockslides have occurred in parts of the park that are heavily used by visitors. To reduce the potential impact of future events, the National Park Service is working to understand the rockfall and rockslide hazards. Predicting rockfall events is not possible, but information about how, where and why they occur can be used to improve visitor safety.

Most rockfalls in Yosemite are triggered by earthquakes, rainstorms, or rapid snow melt. However, many rockfalls occur without an obvious triggering event. Some are probably associated with gradual stress release and weathering of granitic rocks in the valley walls. These processes have been active enough to produce a talus slope over 100 meters thick at the base of some slopes.

Yosemite Valley: A classic view of Yosemite Valley showing the tall, steep granite cliffs that are prone to rockfalls and rockslides. This view, looking east up the Yosemite Valley, shows El Capitan on the left, Half Dome in the far distance, and Bridalveil Fall on the right. The Merced River meanders through the forested valley floor. Photo copyright iStockphoto / S. Greg Panosian.

Recent Rockfall Activity

"In 2009, there were 52 documented rock falls in Yosemite, with an approximate cumulative volume of 48,120 cubic meters (142,000 tons). The vast majority of this volume was associated with rock falls occurring in March from Ahwiyah Point near Half Dome. The largest of these had an approximate volume of 45,300 cubic meters (about 134,000 tons), making it the largest rock fall in Yosemite Valley in 22 years. The impact of the falling rock generated ground-shaking similar to a magnitude 2.5 earthquake. Other notable 2009 rock falls occurred in August and September from the Rhombus Wall immediately north of the Ahwahnee Hotel, for a cumulative volume of about 1,200 cubic meters (roughly 3,600 tons)." Quoted from the National Park Service website (link).

Yosemite rockfall: Spectacular rockfall in Yosemite photographed by Herb Dunn on August 6, 2006. View a sequence of photos that document the fall from start to finish, and read what Herb experienced while bravely taking the photos: Click here.

How to Survive a Rockfall

"Rock-fall hazard zones occur throughout the park near any cliff faces. If you witness a rock fall from the Valley floor, quickly move away from the cliff toward the center of the Valley. If you are near the base of a cliff or talus slope when a rock fall occurs above, immediately seek shelter behind the largest nearby boulder. After rocks have stopped falling, move quickly away from the cliff toward the center of the Valley. Be aware that rock falls are inherently unpredictable and may happen at any time. Pay attention to warning signs, stay off of closed trails, and, if unsure, keep away from the cliffs." Quoted from the National Park Service website (link).

NPS Response to Rockfall Studies

The National Park Service is learning from their rockfall research program and using that information to make the Park a safer place to visit. After studying rockfalls in the Curry Village area in 2008, the Park Service determined that over 200 tent and cabin sites were within rockfall hazard areas and closed them permanently. These studies continue in other parts of the park.

| More Landslides |

|

Debris Flow Hazards |

|

Landslides |

|

Yosemite Rockfall Photos |

|

Largest Landslides |

|

Debris Flows |

|

Gifts That Rock |

|

Homeowners Insurance and Landslides |

|

Lahars |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|