Triboluminescence: YouTube video demonstration of triboluminescence. We use two pieces of milky quartz to produce a few flashes of light. You can easily find other minerals that exhibit triboluminescence. About 50% of all crystalline substances exhibit the property [1]. Safety glasses recommended if you do the demonstration yourself.

What is Triboluminescence?

Triboluminescence is a flash of light produced when a material is subjected to friction, impact or breakage. The phenomenon is also known as fractoluminescence and mechanoluminescence. Triboluminescence is common in minerals. About 50% of crystalline materials are thought to exhibit the property. It is also observed in many noncrystalline materials [1].

How to Demonstrate Triboluminescence

A very easy way to observe triboluminescence is to get two milky quartz pebbles that are large enough to easily hold and rub together with a bit of force. Take them into a darkened room and stand in the dark for a few minutes to allow your eyes to adjust to the darkness. You don't need total darkness but the less light the better.

Hold one piece of quartz in your left hand and the other piece in your right hand. Firmly press an edge of one piece of quartz against the other and while holding firm pressure, quickly drag it across the surface in a motion similar to what you would use to strike a large match. Don't be wimpy. Hold firm pressure while you quickly drag one pebble across the surface of the other. If you do this properly and if you have pieces of quartz that are triboluminescent, you will see a brief flash of light that penetrates deeply into the translucent quartz.

Experiment with different speeds, different amounts of pressure, and directions of drag to maximize the flash of light. Some specimens will also produce small amounts of light if you bang them together or rub them against one another. You can also experiment with different minerals to see if they are triboluminescent. You will probably find many minerals that exhibit the property.

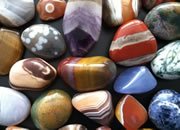

The best way to learn about minerals is to study with a collection of small specimens that you can handle, examine, and observe their properties. Inexpensive mineral collections are available in the Geology.com Store. Image copyright iStockphoto / Anna Usova.

Triboluminescence in Minerals

Triboluminescence is present in quartz; however, the strength of the phenomenon varies from specimen to specimen. Triboluminescence is well known in sphalerite, fluorite, calcite, muscovite, and many feldspar minerals. Some specimens of common opal produce a bright orange flash.

Test a few specimens yourself. Don't forget to wear safety glasses, and be aware that this test will scratch your specimens. You will probably discover lots of specimens of various minerals that are triboluminescent. We have found that the flash of light is brightest when we use specimens that are transparent or very translucent. These specimens allow the light to penetrate deeply, making the flash easier to observe.

For years we have observed flashes of light while cutting lapidary rough on a rock saw or shaping it on a diamond wheel. We originally thought this light was incandescence (an emission of light from a hot object), but now we think that at least some of that light was triboluminescence.

Triboluminescence is not a good property to use for mineral identification. Some specimens of a mineral might exhibit the property and other specimens will not.

| Triboluminescence Information Sources |

|

[1] The Effect of Triboluminescence in Everyday Materials: Andrew DeMiglio, Kent State University, PowerPoint Presentation posted online, accessed March 2013.

[2] Wintergreen Candy and Other Triboluminescent Materials: Linda M. Sweeting, Department of Chemistry, Towson University, Scientific Experiments at Home website series, September 1998. [3] Cape Cod's "Magic" Quartz Pebbles: Robert N. Oldale, United States Geological Survey, Coastal and Marine Geology Program, website article, May 2007. Hosted on the Internet Archive. [4] Candy Triboluminescence: Anne Marie Helmenstine, Ph.D., ThoughtCo.com website article, last accessed September 2022. [5] Assessment of Triboluminescent Materials for In-Situ Health Monitoring: Tarik J. Dickens, Master of Science thesis submitted to the College of Engineering at Florida State University, 2007. |

Why is Light Produced?

The phenomenon of triboluminescence is poorly understood. Some researchers believe that scratching or hitting materials together provides an input of energy that excites electrons within the materials. When the electrons fall from their excited state, a flash of light is produced [2]. Others believe that triboluminescence is similar to lightning and caused by an electrical current generated by force applied to the materials. The electrical current travels through the material, causing molecules of gas trapped within the crystal to glow [3].

The flashes of light produced by triboluminescent minerals is usually white or orange, but other colors are possible. We may not see all of the light that is produced because some of it could have wavelengths that are outside of the visible spectrum of humans [2].

Wint O Green Lifesavers?

An interesting material that exhibits a blue triboluminescence is Wint O Green Lifesavers. If you crush them with a pair of pliers in a dark room, you should see some nice blue flashes of light. The crystalline sugar in the candy is thought to be the source of the triboluminescence, and the methyl salicylate (wintergreen flavoring) produces a blue fluorescence [4]. Many other types of hard sugar candy exhibit triboluminescence.

Practical Uses for Triboluminescence

Triboluminescent materials can be used to detect structural damage. If triboluminescent materials are embedded in a composite, they will generate light if the composite begins to experience structural failure. A sensor will detect the light and report that failure has occurred. This monitoring can detect failure in its early stages because many composite materials begin to fracture at the microscopic level far in advance of complete failure.

These methods are expensive to implement and can only be used in equipment where detecting early-stage failure can result in high-value savings. Component parts of spacecraft, aircraft, naval vessels, buildings, dams, bridges and other critical structures are where these methods might be used [5].

| More Minerals |

|

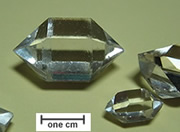

Herkimer Diamonds |

|

The Acid Test |

|

Tumbled Stones |

|

Zircon |

|

Fool*s Gold |

|

Kyanite |

|

Rock Tumblers |

|

Rhodochrosite |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|