Home » Oil and Gas » Utica Shale

Utica Shale - The Natural Gas Giant Below the Marcellus

Stacked plays in the Appalachian Basin produce multiple natural gas pay zones.

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD

Figure 1: The green area on this map marks the geographic extent of the Utica Shale. Included in this extent are two laterally equivalent rock units: the Antes Shale of central Pennsylvania and Point Pleasant Formation of Ohio and western Pennsylvania. These rocks extend beneath several U.S. states, part of Lake Erie, part of Lake Ontario and part of Ontario, Canada. If developed throughout this extent, the Utica Shale gas play will be larger than any natural gas field known today.

The thin yellow line on the map outlines the geographic extent of the Marcellus Shale Gas Play. This map clearly demonstrates that the Utica Shale has a geographic extent that is much greater than

the Marcellus Shale.

This map was compiled by Geology.com using data provided by the Energy Information Administration [1] and the United States Geological Survey [2].

What is the Utica Shale?

The Utica Shale is a black, calcareous, organic-rich shale of Middle Ordovician age that underlies significant portions of Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, New York, Quebec and other parts of eastern North America (see Figure 1). In the subsurface, the Utica Shale is located a few thousand feet below the Marcellus Shale, which has become widely known as a source of natural gas (see Figure 2).

The Utica Shale is currently receiving a lot of attention because it is yielding large amounts of natural gas, natural gas liquids and crude oil to wells drilled in eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania. The United States Geological Survey's mean estimates of undiscovered, technically recoverable unconventional resources indicate that the Utica Shale contains about 38 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, about 940 million barrels of oil, and 208 million barrels of natural gas liquids [14].

Geologists have long considered the Utica Shale to be an oil and natural gas source rock. Natural gas and oil generated in the Utica Shale have migrated upwards and are produced from reservoirs in overlying rock units. An even greater quantity of oil and natural gas is still trapped in the Utica Shale.

The Utica Shale has not been extensively developed for two reasons: 1) its great depth over much of its geographic extent, and, 2) its limited ability to yield gas and oil to a well because of its low permeability. This is starting to change as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing are used to stimulate production. These methods were not extensively used in the Utica Shale prior to 2010.

Figure 1a: This map shows an example of the extremely high drilling density of horizontal wells in the eastern Ohio portion of the Utica Shale. There must be a "sweet spot" down there!

Related: Learn About Mineral Rights

The Marcellus was the Opening Act

The Marcellus Shale is another organic-rich rock unit that historically attracted limited commercial interest because of its low permeability. However, that changed in 2003 when Range Resources began drilling productive wells into the Marcellus using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technologies. These methods solved the low permeability problem and produced fractures that allowed fluids to flow through the rock unit and into a well.

Now, just a few years later, the Marcellus Shale has become one of the world's largest natural gas fields, and the Utica Shale - located a few thousand feet below the Marcellus - has become a new drilling target.

The oil and natural gas potential of the Utica Shale is not fully understood. It has only been seriously drilled in eastern Ohio since 2010 (see Figure 1a). However, it is already becoming a significant oil, natural gas and natural gas liquids producer. It is more geographically extensive than the Marcellus (see Figure 1), it is thicker than the Marcellus (see Figure 6), and it has already proven its ability to yield commercial quantities of natural gas, natural gas liquids and crude oil.

It is impossible to say at this time exactly how large the Utica Shale resource might be because it has only been lightly drilled in western Pennsylvania and in the St. Lawrence Lowlands of Quebec, Canada. In central Pennsylvania, where the Utica is deep below the Marcellus, it is virtually untested with horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Limited testing suggests that the Utica Shale will be an enormous fossil fuel resource.

Figure 2: Generalized stratigraphic sequence of rock units surrounding the Utica Shale and Marcellus Shale. The Utica and Marcellus are so geographically extensive that it is impossible to present a stratigraphic sequence that would be correct in all areas. This diagram presents a generalized sequence of rocks that might be present in central and western Pennsylvania. Image by Geology.com.

How Deep is the Utica Shale?

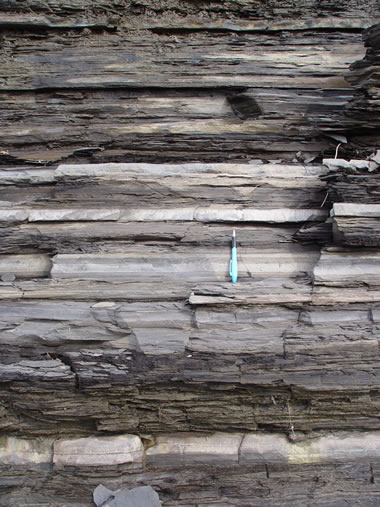

The Utica Shale is much deeper than the Marcellus. The Utica Shale elevation map (shown as Figure 3 in the right column of this page) has contour lines that show the elevation of the base of the Utica Shale in feet below sea level. In some parts of Pennsylvania, the Utica Shale can be over two miles below sea level. However, the depth of the Utica Shale decreases to the west into Ohio and to the northwest under the Great Lakes and into Canada. In these areas the Utica Shale rises to less than 2000 feet below sea level. Beyond the potential source rock areas, the Utica Shale rises to Earth's surface and can be seen in outcrop. An outcrop photo of the Utica Shale near the town of Donnacona, Quebec, Canada is shown as Figure 4.

Most of the major rock units in the Appalachian Basin are thickest in the east and thin towards the west. The rock units that occur between the Marcellus Shale and the Utica Shale follow this trend. In central Pennsylvania, the Utica can be up to 7000 feet below the Marcellus Shale, but that depth difference decreases to the west. In eastern Ohio the Utica can be less than 3000 feet below the Marcellus.

These depth relationships of the Utica Shale and the Marcellus Shale are shown in the generalized cross sections shown below as Figure 5a and Figure 5b.

Figure 3: Approximate elevation for the base of the Utica Shale (top of the Trenton/Black River Limestones). Elevations shown on the map are feet below sea level.

This map was compiled by Geology.com using data provided by the Energy Information Administration [1], the United States Geological Survey [2], and the Pennsylvania Geological Survey [3].

Figure 5a: The cross section above shows the subsurface position of the Marcellus Shale, Utica Shale and the continental basement rock. The line of cross section is shown as line A-B on the inset map. Note that the Utica Shale is about 2000 feet below the Marcellus under eastern Ohio but about 6000 feet below the Marcellus in south-central Pennsylvania. Also note that the Marcellus Shale potential source rock does not extend as far into Ohio as the Utica.

This cross section was compiled by Geology.com using data provided by the Energy Information Administration [1], the United States Geological Survey [2], the Pennsylvania Geological Survey [3], and the U.S. Department of Energy [4].

Figure 4: Photograph of the Utica Shale near the town of Donnacona, Quebec, Canada. Dark beds are shale, light beds are limestone. Part of the dark color in the Utica Shale comes from organic matter. A writing pen is shown for scale. Image and caption by The National Energy Board of Canada; from A Primer for Understanding Canadian Shale Gas. [10]

Figure 5b: The cross section above shows the subsurface position of the Marcellus Shale, Utica Shale and the continental basement rock. The line of cross section is shown as line A-B on the inset map. Note that the Utica Shale is about 1800 feet below the Marcellus under western New York but about 5000 feet below the Marcellus in south-central Pennsylvania. Also note that the Marcellus Shale potential source rock does not extend as far into New York as the Utica.

This cross section was compiled by Geology.com using data provided by the Energy Information Administration [1], the United States Geological Survey [2], the Pennsylvania Geological Survey [3], and the U.S. Department of Energy [4].

Figure 6: Thickness map of rocks present between the top of the Trenton/Black River Groups and the top of the Utica Shale. In some areas the Point Pleasant Shale and the Antes Shale are included in this thickness.

This map was compiled by Geology.com using data provided by the Energy Information Administration [1] and the U.S. Department of Energy [4].

Thickness of the Utica Shale

The thickness of the Utica Shale is variable. Throughout most of its extent, it ranges in thickness from less than 100 feet to over 500 feet. Thickest areas are on the eastern side of its extent, and it generally thins to the northwest. A thickness map of the Utica Shale is shown as Figure 6. Although thickness of a rock unit is important in determining its oil and gas potential, the organic content, thermal maturity and other characteristics must all be favorable.

Organic Content of the Utica Shale

The Utica Shale is an organic-rich rock unit. The organics are what give it a dark gray to black color - and hydrocarbon potential. The amount of organic material in the shale varies throughout its extent and also varies vertically within the rock unit.

A map of the regional variation in total organic carbon is shown as Figure 7. The organic carbon content is generally highest in the center of the rock unit's extent and decreases towards its margins.

Figure 7: Total Organic Carbon content of the Utica Shale and equivalent rocks (weight percent). This map shows that the total organic carbon content is highest (greater than 3%) in the approximate center of the geographic extent. High total organic carbon values are often correlated with a high potential of oil and natural gas generation.

This map was compiled by Geology.com using data from the United States Geological Survey [14].

Figure 10: Conodont Alteration Index Map of the Utica Shale and equivalent rocks. CAI correlates with the thermal maturity of the rocks. CAI values between 1 and 2 are normally associated with the presence of crude oil, while CAI between 2 and 5 are normally associated with the presence of natural gas.

This map was compiled by Geology.com using data from the United States Geological Survey [14].

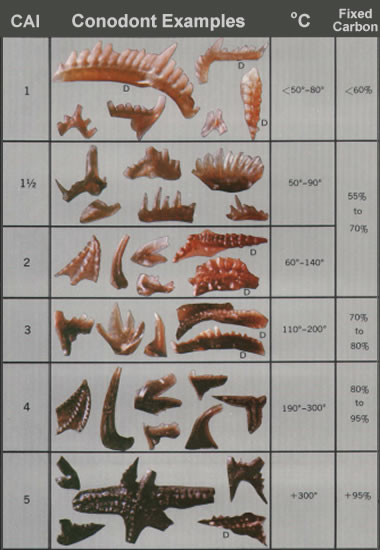

Figure 8: Examples of color alteration in conodont fossils. Image by USGS. [16]

| ||

Conodont Alteration Index of the Utica Shale

Conodonts are microfossils of eel-like animals that lived in marine environments from the Cambrian through Triassic Periods. They are composed of calcium phosphate and range in size from about 0.2 to 6 millimeters. (See Figure 8.) They are useful in determining the age of a rock unit and correlating rock units from one location to another.

When heated, conodonts change color through the sequence shown in Figure 9, according to the temperature of the surrounding rocks. This progressive color change has been linked to rock temperatures by the "conodont alteration index" (or "CAI"). The color progression is not reversible and records the maximum temperature to which the rocks have been heated.

As the rocks are heated, organic materials in the rocks are modified by rising temperature. At a CAI of 1, organic materials in the rocks yield crude oil. At a CAI of 2, oil is starting to convert into natural gas.

The significance of Utica Shale CAI is shown on the map in Figure 10. The area between CAI 1 and CAI 2 is where crude oil is likely to be found in the Utica Shale. Where the CAI is greater than 2, natural gas is likely to be the dominant hydrocarbon.

Figure 11: Location of the oil and gas assessment units for the Utica Shale determined by the United States Geological Survey. The area in green is where wells are likely to encounter crude oil. The area in pink is where natural gas is likely to be the dominant hydrocarbon.

This map was compiled by Geology.com using data from the United States Geological Survey [14].

USGS Oil and Gas Resource Assessment

In September 2012, the United States Geological Survey published an "Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Ordovician Utica Shale of the Appalachian Basin Province, 2012". [14]

They identified two assessment units in the Utica Shale. The geographic areas covered by these units are shown on the map in Figure 11. Their Utica Shale Gas Assessment Unit (Gas AU) is defined where the thermal maturity of the organic matter is greater than a CAI of 2, and where the total organic carbon is greater than 1 weight percent.

The Utica Shale Oil Assessment Unit (Oil AU) is defined where the thermal maturity of the organic matter is greater than CAI of 1 but less than a CAI of 2, and where the total organic carbon is greater than 1 weight percent.

Figure 12: Utica Shale USGS "sweet spots." This map shows the expected optimal areas for developing the Utica Shale according to the USGS assessment of 2012. Generally, these areas are where the Total Organic Carbon (TOC) content of the Utica Shale is high. (See Figure 7 for TOC map.)

This map was compiled by Geology.com using data from the United States Geological Survey [14].

Figure 7: Utica Shale drilling permits issued in Ohio between September 2010 and October 2013. Chart prepared by Geology.com using data from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

Utica Shale in Eastern Ohio

Most of the drilling activity in the Utica Shale has occurred in eastern Ohio. This geographic area attracted interest for a variety of reasons which include: 1) the Utica Shale is only a few thousand to several thousand feet below the surface; and, 2) wells drilled into the Utica Shale were yielding significant amounts of natural gas liquids and crude oil. Since 2010 oil and natural gas companies have spent billions of dollars acquiring Utica Shale acreage in eastern Ohio and drilling wells.

The generalized cross sections for the Utica and Marcellus Shale shown above as Figures 5a and 5b illustrate why the Utica is being developed in some parts of Ohio and Canada instead of the Marcellus.

Where cross section 5a traverses the Pennsylvania-Ohio state boundary, the Marcellus Shale is above the Utica and is preferentially drilled because it is a shallower target. However, the productive portion of the Marcellus Shale does not extend into central Ohio - but the Utica Shale does. In those areas the Utica Shale is less than one mile below the surface.

The Utica Shale is proving to be rich in oil and natural gas liquids. On an energy-equivalent basis, these wells are worth significantly more than wells that produce natural gas alone. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources estimates a recoverable Utica Shale potential between 1.3 and 5.5 billion barrels of oil and between 3.8 and 15.7 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. Companies interested in drilling the Utica Shale have been flooding ODNR with permit applications (see chart).

Press releases from Chesapeake Energy reported several wells with peak rates of over five million cubic feet of natural gas per day along with hundreds to thousands of barrels of natural gas liquids. Optimism based upon these drilling results prompted Chesapeake to claim that their Utica Shale assets added over $15 billion in value to the company.

This is a valuation of at least $12,000 per acre!

Having achieved successful results from recent drilling activities in eastern Ohio, Chesapeake is announcing the discovery of a major new liquids-rich play in the Utica Shale. Based on its proprietary geoscientific, petrophysical and engineering research during the past two years and the results of six horizontal and nine vertical wells it has drilled, Chesapeake believes that its industry-leading 1.25 million net leasehold acres in the Utica Shale play could be worth $15 - $20 billion in increased value to the company.[12]

| Utica Shale References |

|

[1] Natural Gas Maps: Exploration, Resources, Reserves and Production: United States Energy Information Administration, www.eia.gov.

[2] Assessment of Appalachian Basin Oil and Gas Resources: Utica-Lower Paleozoic Total Petroleum System: Robert T. Ryder, United States Geological Survey, Open-File Report 2008-1287. [3] The Geology of Pennsylvania, Charles H. Schultz, editor; Pennsylvania Geological Survey, Special Publication 1, 1999, 888 pages. [4] Source Rock Distribution and Total Organic Carbon Content: From: Patchen, D.G., and others, 2006, A geologic play book for Trenton-Black River Appalachian Basin exploration: Final report prepared for U.S. Department of Energy, contract no. DE-FC26-03NT41856. [5] Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: U.S. Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory, April 2009. [6] Shale: Description of Sedimentary Rocks, Geology.com. [7] What is Shale Gas? Energy Information Administration, December 2010. [8] Geologic Unit: Utica: United States Geological Survey GEOLEX Database. [9] Update on Regional Assessment of Gas Potential in the Devonian Marcellus and Ordovician Utica Shales of New York: Richard Nyahay, James Leone, Langhorne Smith, John Martin, and Daniel Jarvie; Reservoir Characterization Group at the New York State Museum; Search and Discovery Article #10136; October 2007. [10] A Primer for Understanding Canadian Shale Gas: Energy Briefing Note, National Energy Board of Canada, November 2009, 23 pages. [11] The Marcellus & Utica Shale Plays in Ohio: PowerPoint Presentation by Larry Wickstrom, Chris Perry, Matt Erenpreiss and Ron Riley; Ohio Geological Survey, ooga.org, 2011. [12] Financial and Operational Results for the 2011 Second Quarter: Chesapeake Energy Corporation, July 2011. [13] Oil and natural gas drilling in Ohio on the rise. U.S. Energy Information Administration, October 11, 2011. [14] Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Ordovician Utica Shale of the Appalachian Basin Province, 2012: United States Geological Survey, Fact Sheet 2012-3116, September 2012. [15] Landowners and Oil and Gas Leases in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, Fact Sheet 8000-FS-DEP2834, November 2012. [16] Conodont Color Alteration - an Index to Organic Metamorphism: Anita G. Epstein, Jack B. Epstein, and Leonard D. Harris; United States Geological Survey, Professional Paper 995, 1977. |

Utica Shale in Pennsylvania

Most of the shale drilling activity in Pennsylvania has targeted the Marcellus Shale, which is above the Utica Shale. In some parts of Pennsylvania the Marcellus Shale is immediately above the Onondaga Limestone. The Utica Shale is located beneath the Onondaga. Why is that significant? Here is a quote from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection website that explains:

"Your oil or gas could be produced or captured from a well outside your property tract boundaries. In fact, your only protection is if your oil or gas property is subject to the Oil and Gas Conservation Law, 58 P.S. § 401.1 et seq. If so, the gas on your property could be included in a unitization or pooling order issued by the Commonwealth at the behest of a producer on a neighboring tract. That well operator would then have to pay you a production royalty based on your prorated share of the production from the well, depending on how much of your tract was deemed to be contributing to the well's pool. This law applies to oil or gas wells that penetrate the Onondaga horizon and are more than 3,800 feet deep."

Video Interview: Potential of Other Gas Shale Formations in the Northeastern United States. Pennsylvania State University geologist Dr. Terry Engelder describes historical and recent drilling results for the Utica Shale.

Future Development of the Utica Shale

Two important challenges for developing the Utica Shale in Pennsylvania are its significant depth and a lack of information. In areas where the Marcellus Shale is present, the Utica Shale is probably going to be a resource of the distant future. The Marcellus Shale is less expensive to develop, and companies will focus on it before setting their sights on a deeper target with an uncertain payoff.

However, in areas where the Marcellus Shale has been developed, the Utica will have an infrastructure advantage. Drilling pads, roadways, pipelines, gathering systems, surveying work, permit preparation data and landowner relationships might still be useful for developing the Utica Shale.

The Utica Shale underlies parts of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. These areas likely contain natural gas. It is possible that offshore drilling will occur in the lakes in the very distant future.

Hydraulic fracturing: Video by Questerre Energy that explains how hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling will be used to develop the Utica Shale in Quebec, Canada.

| More Oil |

|

The Doorway to Hell |

|

Oil Sands |

|

Shale Gas Resources |

|

Gifts That Rock |

|

Horizontal Drilling |

|

Oil and Gas Rights |

|

Natural Gas Prices |

|

Oil Shale |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|