Home » Rocks » Sedimentary Rocks » Chalk

Chalk

A marine limestone composed mainly of foraminifera and algal remains.

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD

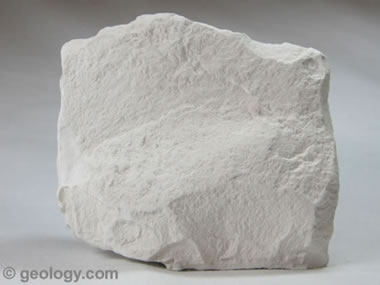

Limestone Chalk: A fine-grained, light-colored limestone chalk formed from the calcium carbonate skeletal remains of tiny marine organisms.

What Is Chalk?

Chalk is a variety of limestone composed mainly of calcium carbonate derived from the shells of tiny marine animals known as foraminifera and from the calcareous remains of marine algae known as coccoliths. Chalk is usually white or light gray in color. It is extremely porous, permeable, soft and friable.

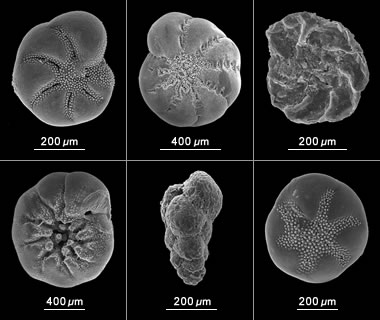

Benthic Foraminifera: Scanning electron microscope views of six different benthic foraminifera. Clockwise from top left: Elphidium incertum, Elphidium excavatum clavatum, Trochammina squamata, Buccella frigida, Eggerella advena, and Ammonia beccarii. The calcium carbonate shells from organisms like these can accumulate to form chalk. Images by the United States Geological Survey.

How Does Chalk Form?

Chalk forms from a fine-grained marine sediment known as ooze. When foraminifera, marine algae, or other organisms living on the bottom or in the waters above die, their remains sink to the bottom and accumulate as ooze. If most of the accumulating organic debris consists of calcium carbonate, then chalk will be the type of rock that forms from the ooze. However, if the accumulating organic debris comes from diatoms and radiolarians, the ooze will consist mainly of silica, and the rock type that forms will be diatomite.

Extensive deposits of chalk are found in many parts of the world. They often form in deep water where clastic sediments from streams and beach action do not dominate the sedimentation. They can also form in epeiric seas on continental crust and on the continental shelf during periods of high sea level.

Chalk is widely known among the people of western Europe and a few other parts of the world because it is a bright white rock that can form vertical cliffs along shorelines. The chalk cliffs are eroded at water level by wave action, and as the base of the cliff is undercut, collapses occur when the undercutting reaches a vertical joint or other plane of weakness.

The spectacular cliffs on both sides of the English Channel are composed of chalk. They are known as the "White Cliffs of Dover" on the United Kingdom side of the Channel and the Cap Blanc-Nez along the coast of France. The English Channel Tunnel, nicknamed "The Chunnel", that connects England and France was bored through the West Melbury Marly Chalk, a thick and extensive chalk unit that underlies the area.

Chalk Cliffs: Things like fossils and flint can often be found at chalk cliffs. As the soft chalk weathers away, flint nodules fall to the beach below. Image of chalk cliffs along the Baltic Sea, photo copyright iStockphoto / hsvrs.

Cretaceous: A Time of Chalk

Much chalk was deposited during the Cretaceous Period of geologic time. It was a time of global high sea levels that began at the end of the Jurassic Period about 145 million years ago and the beginning of the Paleogene Period about 66 million years ago. During the Cretaceous, warm waters of epeiric seas, seas that flooded continental crust during sea level highs, existed in many parts of the world.

Warm waters of the epeiric seas facilitated chalk deposition because calcium carbonate is more soluble in cold water rather than warm water, and because organisms that produce calcium carbonate skeletal debris will more actively produce in warm water. More chalk formed during the Cretaceous Period than in any other period in geologic history. The Cretaceous received its name after the Latin word creta, which means "chalk".

Coarse Chalk: A specimen of chalk with a coarse grain size from the Cretaceous-age Kristianstad Basin collected at a gravel pit near the community of Luneburg, northern Germany. This specimen is from the geological collection of the City Museum of Berlin, and the image is used under a Creative Commons license. Click to enlarge.

Identifying Chalk

The keys to identifying chalk are its hardness, its fossil content, and its acid reaction. At a glance, diatomite and gypsum rock have a similar appearance. An examination with a hand lens will often reveal the fossil content, separating it from gypsum. Its reaction with dilute (5%) hydrochloric acid will separate it from both gypsum and diatomite.

The acid reaction will surprise you if you are used to testing other types of limestone and have never tested chalk. When you apply a drop of acid, capillary action pulls it deep into pore spaces of the specimen. There, the enormous surface area of calcium carbonate that contacts the drop of acid usually produces a spectacular effervescence. Instead of holding the specimen in your hand during the test, place it on surface that will not be damaged by the acid, with a couple paper towels beneath it. You don’t want to have the specimen in your hand and be startled by the effervescence.

Oil and Gas Production from Chalk: Map showing the location of oil and gas production in the Austin Chalk of Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi. Fields are shown in yellow, well locations are shown in green and red. Image by the United States Geological Survey. [1] Click to enlarge.

Porosity and Permeability of Chalk

At a microscopic level, there can be a lot of space between the fossil particles that make up chalk. Land underlain by chalk directly below the soil is often well drained. In these areas, water that infiltrates into the soil encounters the top of the chalk and easily flows into the chalk's pore spaces. It then flows downward to the water table and then follows the direction of groundwater flow to a stream or another body of surface water. In some areas, people drill water wells into subsurface chalk layers for residential, commercial, and community water supplies.

In areas where oil and natural gas form in the subsurface, the pore spaces of chalk can serve as a reservoir. Many oil and gas fields are located where subsurface chalk units serve as reservoirs. The Austin Chalk is a subsurface rock unit beneath parts of Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. It yields oil and natural gas from both conventional and continuous reservoirs. [1]

| Chalk Information |

|

[1] Geologic Models and Evaluation of Undiscovered Conventional and Continuous Oil and Gas Resources -- Upper Cretaceous Austin Chalk, U.S. Gulf Coast: by Krystal Pearson, United States Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations Report 2012-5159, 2012, 26 pages. |

Blackboards and Chalk

Small pieces of chalk have been used by students for over 1000 years for writing on small slates and large classroom panels known as "blackboards". It is an inexpensive and erasable writing material and the most widely known use of chalk. Much of the early blackboard writing was done with pieces of natural chalk or natural gypsum.

Today pieces of natural chalk and natural gypsum have been replaced by sticks manufactured from natural chalk; sticks manufactured using other sources of calcium carbonate; or sticks manufactured using natural gypsum. Gypsum chalk is the softest and writes smoothest; however, it produces more dust than calcium carbonate chalk. Calcium carbonate chalk is harder, requires more pressure to produce wide marks, and makes less dust. It is sometimes marketed as "dustless chalk" but that description is not quite true. Even though most chalk today is not made from mineral chalk, people still use the name "chalk" for this familiar writing material.

| More Rocks |

|

Tumbled Stones |

|

Fossils |

|

Geodes |

|

The Rock Used to Make Beer |

|

Topo Maps |

|

Difficult Rocks |

|

Fluorescent Minerals |

|

Sliding Rocks on Racetrack Playa |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|