Home » Volcanoes » Cinder Cones

Cinder Cones

The smallest, simplest, and most common type of volcano

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD

Cumbre Vieja Volcano on the Canary Island of La Palma, has been erupting cinders, volcanic ash and lava from multiple cinder cones high on Cumbre Vieja Ridge. These eruptions are powered by jets of gas escaping from a magma chamber below. The jets of gas blow cinders and volcanic ash high into the air, and the winds (blowing from left to right in this photo) carry the cinders and ash until they rain down on communities and cultivated areas in the lowland below. Lava flows emerging from the same vents flow downhill, destroy everything in their path, and cover the landscape in black basalt. Photo copyright by Addictive Stock Creatives / Alamy Stock Photo.

Cinder Cone Volcano: A photograph of Parícutin, the world's most famous cinder cone. It erupted and grew between 1943 and 1952 and is located near the city of Uruapan, Mexico. Today it is a volcano that is 1,391 feet in height and surrounded by about 90 square miles of lava flows. Photo by Brian Overcast / Alamy Stock Photo.

What Are Cinder Cones?

Cinder cones, also known as pyroclastic cones, are the smallest and the simplest type of volcano. They are the world's most common volcanic landform. As the name "cinder cone" suggests, they are cone-shaped hills made up of ejected igneous rocks known as "cinders".

These small volcanoes usually have a circular footprint, and their flanks usually slope at an angle of about 30 to 40 degrees. Most cinder cones have a bowl-shaped crater at the top.

Cinder cones are found in many parts of the world. Countries that have many cinder cones include: Australia, Canada, Chile, France, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Spain (Canary Islands), Turkey, and the United States.

Table of Contents

Cinder Eruption at Cumbre Vieja: Volcanic eruptions began on September 19, 2021 at Cumbre Vieja Ridge on the Canary Island of La Palma. Numerous cinder cones have developed along the crest of the ridge. High-pressure gas jets from these volcanoes blow cinders and volcanic ash high into the air. The wind (blowing from left to right in this photo) carries them to fall and blanket the landscape below - covering homes, roads, agricultural fields, schools, and businesses. Thousands of buildings have been buried or cut off from road access. Photo by Marcos del Mazo / Alamy Stock Photo.

How Do Cinder Cones Form?

Cinder cones form when molten rock known as "magma" approaches Earth's surface. The magma that forms cinder cones contains a tremendous amount of dissolved gas - and that gas is what powers a cinder cone eruption.

Some gas-charged magmas contain several percent volcanic gas on the basis of weight.

Think about that - several percent gas - on the basis of weight.

That is a tremendous amount of gas!

When the magma breaks through Earth's surface, the confining pressure on the gas is suddenly removed. The release of confining pressure causes the gas to expand as an explosive eruption that launches a spray of molten rock into the air.

The molten rock cools as it flies through the air, and the cinders rain down onto the surrounding landscape. Most of the cinders land close to the vent, and these are what build the cone. Many cinder cones blast cinders a mile or more from the vent, and the wind often assists in their spread.

Scoria Cinder Cone: Artistic drawing illustrating the subsurface magma source and layer-by-layer build-up of scoria in a cinder cone eruption. Image by USGS.

How Large Are Cinder Cones?

Most cinder cones are only a few dozen to a few hundred feet tall. Some of the largest are over 1000 feet tall. Some cinder cones grow to over one mile in diameter at their base, but most are smaller.

Cinder cones are small because the eruptions that build them are usually brief and produce a small volume of ejecta. Many cinder cones have just one episode of activity.

Some cinder cones grow larger over a sequence of eruptions - with each successive eruption adding another layer of cinders. The accompanying illustration shows the internal structure of a cinder cone that has grown taller and wider from several eruptive episodes.

Cinders at Mount Etna: A ground cover of cinders on the flank of Mount Etna volcano, island of Sicily, Italy. A "rock name" for these cinders would be scoria. Photograph by Ji-Elle, displayed here under a Creative Commons License.

An Eruption of Cinders: A small explosion at Mount Etna in 2014 launches a shower of molten rock into the air. The resistance it encounters as it flies through the air tears the molten rock into smaller pieces. It falls to earth as hot cinders or as molten blobs. Don't get this close to an erupting volcano! Photograph by Simone Genovese / Alamy Stock Photo.

What Are Cinders?

"Cinders" are small pieces of igneous rock that have been blown from the vent of a cinder cone. They usually have a composition similar to basalt and contain numerous vesicles. Vesicles are small, round, bubble-like cavities that owe their presence to small amounts of gas that were trapped in the rock at the time of its solidification.

Geologists use the name "scoria" for rocks that have a basaltic composition and a vesicular texture. The names scoria and cinders are often used interchangeably. The color range of cinders goes from black, to dark gray, to deep reddish brown.

These small pieces of rock obtained the name "cinders" because they look like the ash produced in a coal furnace, which English-speaking people have called "cinders" for many generations. Larger pieces are sometimes called "clinkers" for the same reason, and because they sometimes make a "clinking" noise when they impact one another.

Cinder Cone Eruption: A night-time view of Parícutin erupting cinders which are so hot that they are incandescent as they fly through the air - and also after they land. Photo by JSM Historical / Alamy Stock Photo.

However, the proper scientific terminology is to use the name "lapilli" for ejected material with a particle size under 64 millimeters (2.5 inches) and the names "blocks" or "bombs" for material with a particle size over 64 millimeters.

Fine particle sizes are called "volcanic ash" if the material is under 2 millimeters (0.079 inch) and "volcanic dust" or "fine volcanic ash" for material under 0.063 millimeters (0.0025 inch).

Tephra / Pyroclastic Terminology * |

||

| Geologic Name | Coal Furnace Terminology ** | Particle Size |

| Blocks / Bombs | "clinkers" | > 64 mm (2.5 inch) |

| Lapilli | "cinders" | < 64 mm (2.5 inch) |

| Volcanic Ash | "ash" | < 2 mm (.079 inch) |

| Volcanic Dust (Fine Volcanic Ash) |

"ash" | < 0.063 mm (0.0025 inch) |

| * "Tephra" and "pyroclastics" are generalized names used for particles of igneous rocks of various sizes that have been ejected from volcanoes. They are classified by size. The terms "ash" and "dust" communicate a specific size of tephra or pyroclastic particles. These are summarized in the table above. ** Coal furnace terminology is provided for entertainment and the particle sizes are not specific. | ||

What Is Ejecta?

The names "ejecta" and "tephra" and "pyroclastics" are all used for the rock fragments blown from a cinder cone or other type of volcano during an explosive eruption.

Many scientists use the terminology in the accompanying table when they talk or write about materials ejected from a cinder cone or other type of volcanic eruption.

The names in the table are a classification of ejecta according to the particle size. They facilitate accurate communication.

Cinder Cone and Lava Flow: An aerial photo of S P Crater with an ancient basalt flow that extends over 4 miles into the distance. That lava flow emerged from the base of S P Crater about 70,000 years ago (surprisingly, it still look fresh because of the arid climate). S P Crater is about 820 feet tall. Photo by Tom Bean / Alamy Stock Photo.

Do Cinder Cones Make Lava Flows?

Yes, some of them do!

Many cinder cones produce lava flows, but they might not emerge the way you expect.

The first phase of a cinder cone eruption is usually a phase that produces cinders. After the pressurized gas that propels the cinders is exhausted, a second phase might produce a lava flow.

During the second phase, lava emerges from the Earth beneath the cone. However, the pile of cinders is not competent enough to confine the lava to the pipe that connects to the crater. So the lava, like any liquid, starts flowing downhill and "burrows" its way out. It emerges from the base of the cone on its downhill side. The accompanying photo shows a lava flow that emerged through the side of S P Crater near Flagstaff, Arizona.

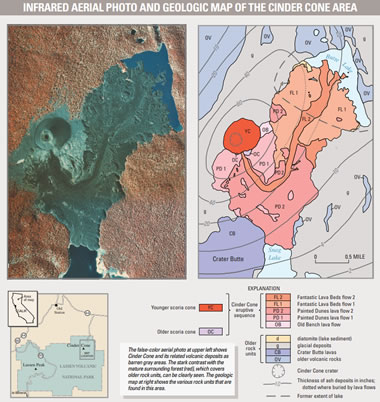

Geologic Map: Cinder Cone and Lava Flows: The image above displays an aerial photo / geologic map pair of a cinder cone and lava flows at Lassen Volcanic National Park, California. From U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 023-00. [3] Click to enlarge.

Geologic Map of a Cinder Cone

The accompanying image displays an aerial photograph / geologic map pair that features a cinder cone and multiple stacked lava flows located in Lassen Volcanic National Park, California. The name of the cinder cone is "Cinder Cone" and it has produced at least five lava flows which have emerged from the base of the cone and flowed out and over one another.

Mapped products of Cinder Cone's eruptions are one small volcanic cone and five lava flows. Geologists of the United States Geological Survey have traced, identified and mapped these deposits. You can study them in an enlarged version of the accompanying image.

You can read about the eruption and these deposits in much more detail in How Old is "Cinder Cone"? - Solving a Mystery in Lassen Volcanic National Park, California; United States Geological Survey Fact Sheet 023-00. If you are a geology major, you should look at this map and visualize the superposition of the lava flows.

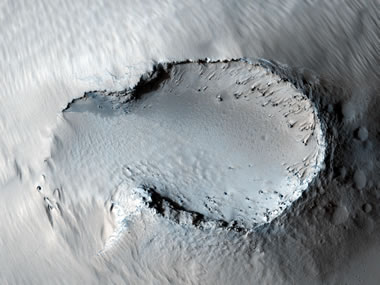

Cinder Cone on Mars: This satellite image shows a possible parasitic cinder cone on the southern flank of Pavonis Mons, a shield volcano on Mars. [2]

Lunar Cinder Cone: A small cinder cone on the surface of the Moon, in northeastern Mare Nubium. The width of the view is about 2.5 miles. This image was captured by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter on May 9, 2014.

Extraterrestrial Cinder Cones

Evidence of past volcanic activity has been found on most planets in our solar system and on many of their moons. We have an article titled "Active Volcanoes of Our Solar System."

Beyond Earth, cinder cones are believed to exist on the Moon, Mars, and Venus. [1] These beliefs are based on the morphology of the volcanoes as viewed on satellite images.

All three of these bodies are known to have volcanic surface features produced by the eruption of silicate magmas, believed to be basaltic in composition.

The Moon, Mars, and Venus have environments that are very different from Earth's. They differ greatly in atmospheric pressure, surface temperature, and the pull of gravity. They also likely differ in the composition of their magmas and their volatile contents.

These differences in environment can influence the size of the cone, its steepness, the abundance of vesicles, the violence of eruption, and many other characteristics of eruptions, cone shape, lava characteristics, and more. [1]

Where Can I See A Cinder Cone?

Cinder cones are found in many parts of the world, including: Australia, Canada, Chile, France, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Spain (Canary Islands), Turkey, and the United States. Volcano tourism has become very popular, however, numerous people have been killed while observing volcanoes.

If you want to travel to see a volcano, a little research can help you to do it safely. A BBC article covers some of the world's most popular volcanoes that have been recently active. If your goal is to see active volcanism, do a little research before your trip - to learn if safe observations are possible.

Safe places to see inactive cinder cones in the United States - and get up close to them - are described below.

Sunset Crater is a cinder cone located in the San Francisco Volcanic Field. If you enlarge this photo, you will see numerous cinder cones in the distance. Photograph by the National Park Service.

Sunset Crater

One of the best places to visit a cinder cone in the United States is at Sunset Crater National Monument near Flagstaff, Arizona. There you can get really close to Sunset Crater, a cinder cone about 1000 feet tall (305 meters), and Lenox Crater, a smaller and older cinder cone that is about 300 feet tall (91 meters). A hiking trail will take you part way up Sunset Crater, but hiking to the top is not allowed.

Sunset Crater is not an active volcano. It formed about 1000 years ago. While you are there, you can get up close and examine many features of the Bonito and Kana-a Lava Flows. You will learn how lava flows can be a significant barrier to humans.

Wizard Island is a cinder cone that was built by numerous eruptions within the Crater Lake caldera. The cone rises to about 755 feet above the average water level of Crater Lake. National Park Service Photo.

Wizard Island

If you visit Crater Lake National Park in south-central Oregon, you will see Wizard Island, a cinder cone on the western end of Crater Lake. Crater Lake formed about 7700 years ago when an enormous volcanic eruption of Mount Mazama emptied a magma chamber below the mountain. The fractured rock above the magma chamber collapsed to produce a collapse caldera over six miles across. The caldera now holds the deepest lake in the United States and the ninth-deepest lake in the world.

Later eruptions within the caldera built a platform on the western end of the lake, where Wizard Island, a cinder cone, is now located. The rim of the cone rises to about 755 feet above Crater Lake's average water level. Visitors can view Wizard Island at many points around the rim of the caldera. During some days of the year, visitors can take a passenger boat trip to the island. They can also hike switchback trails to the rim of the cone for a nice view of the crater and surrounding lake.

| Cinder Cone Information |

|

[1] Comparative Volcanism on the Solid Worlds, by John Merck, article on the University of Maryland website, last accessed October 2022.

[2] Possible Cinder Cone on the Southern Flank of Pavonis Mons, article on the NASA/JPL website, last accessed October 2022. [3] How Old is "Cinder Cone"? - Solving a Mystery in Lassen Volcanic National Park, California: by Michael A. Clynne, Duane E. Champion, Deborah A. Trimble, James W. Hendley II, and Peter H. Stauffer; United States Geological Survey Fact Sheet 023-00; four pages, published in 2000. |

Cinder Cones in the United StatesResearch before you visit! | |

| Volcano | State |

| Albuquerque Volcanic Field | NM |

| Amboy Crater | CA |

| Capulin Volcano National Monument | NM |

| Cinder Cone & Fantastic Lava Beds | CA |

| Cinnamon Butte | OR |

| Craters of the Moon | ID |

| Davis Lake Volcanic Field | OR |

| Hoodoo Butte | OR |

| Indian Heaven | WA |

| Ingakslugwat Hills | AK |

| Koko Crater | HI |

| Lava Butte | OR |

| Mono-Inyo Craters | CA |

| Mount Gordon | AK |

| Mount Tabor | OR |

| Mount Talbert | OR |

| Newberry Volcano | OR |

| Pilot Butte | OR |

| Pisgah Crater | CA |

| Powell Butte | OR |

| Prindle Volcano | AK |

| Puʻuʻōʻō | HI |

| Puʻu Waʻawaʻa | HI |

| Rocky Butte | OR |

| Roden Crater | AZ |

| S P Crater | AZ |

| Schonchin Butte | CA |

| Sunset Crater | AZ |

| Tantalus | HI |

| Twin Buttes | CA |

| Veyo Volcano | UT |

| Vulcan's Throne | AZ |

| Wizard Island | OR |

| Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field | NM |

| More Volcanoes |

|

Where Are the Canary Islands? |

|

Mount Cleveland |

|

Solar System Volcanoes |

|

Dallol Volcano |

|

What is a Maar? |

|

Spectacular Eruption Photos |

|

Stromboli Volcano |

|

Mount St. Helens |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|