Mineraloids

Interesting materials that fall short of meeting the definition of a "mineral"

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD, RPG

Common opal is a mineraloid. It is an amorphous silica with a chemical composition of SiO2.nH2O. It has a conchoidal fracture that is characteristic of an amorphous glass.

Precious Opal is a mineraloid. The play-of-color in opal is produced when light travels through a three-dimensional array of tiny silica spheres within the material. These tiny spheres serve as a diffraction grating that separates the light into its component colors. These spheres are very small and do not constitute an ordered atomic structure.

What Are Mineraloids?

A mineraloid is a naturally occurring, inorganic solid that does not exhibit crystallinity. It may have the outward appearance of a mineral, but it does not have the "ordered atomic structure" required to meet the definition of a mineral. Some mineraloids also lack the "definite chemical composition" required to be a mineral.

To be considered a mineral, a material must meet the following five requirements:

-

1) naturally occurring

2) inorganic

3) solid

4) ordered atomic structure

5) definite chemical composition (can vary within a limited range)

Minerals are "crystalline." In other words, they have an ordered atomic structure. In contrast, mineraloids are "amorphous." This means that their internal atomic structure is not ordered.

Without the ordered atomic structure, mineraloids never produce well-formed crystals. They also do not exhibit the property of cleavage because they lack internal planes of weakness.

Obsidian is a mineraloid. It is a volcanic glass that cools so rapidly that atoms do not have time to arrange themselves into a crystalline solid. Instead, they form an amorphous, randomly bonded network.

Examples of Mineraloids

There are a number of familiar materials that can be classified as mineraloids. For example, opal is an amorphous hydrated silica with a chemical composition of SiO2.nH2O. The "n" in its formula indicates that the amount of water is variable. Therefore, opal is a mineraloid.

Obsidian and pumice are igneous rocks that solidified so rapidly from a melt that their atoms were unable to move into an ordered atomic structure. Instead, they rapidly formed a random network of atoms known as a "glass." Obsidian and pumice are amorphous, and their compositions can vary dramatically from one location to another and from one volcanic eruption to the next. Obsidian and pumice are also mineraloids.

Pele's Hair is the name used for hair-like strands of volcanic glass that sometimes form in areas where lava fountaining, lava cascades and vigorous lava activity occur. They are less than 1/2 millimeter in width, but can be up to two meters in length. They resemble golden-brown human hair in their size, shape and color. They are a mineraloid formed from basaltic lava. Creative Commons photograph by Cm3826.

Pumice is an expanded volcanic glass. It forms during explosive eruptions of gas-charged magma. It is ejected from the volcano in a sudden blast and cools so quickly that bubbles of gas are trapped within the amorphous glass.

Tektites are pieces of black glass formed by an impact somewhere between Australia and Southeast Asia about 800,000 years ago. The specimen in the above photo is a tektite from the Australasian strewnfield. Millions of tektites, ranging from sand-size grains to fist-size nodules, have been found in that area. Their surfaces are often marked with the same surface regmaglypts seen on iron meteorites.

Mineraloids from the Sky

Tektites and moldavites are varieties of natural glass that formed from the impact of an asteroid or comet. These objects struck the Earth at hypervelocity, and the force of their impact produced a tremendous amount of heat energy. The explosion that occurred upon impact flash-melted the target rock and produced a shower of molten material over thousands to millions of square miles. The molten material's temperature dropped quickly as it flew through the air - so quickly that the melts solidified without forming crystals.

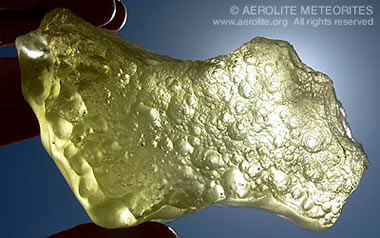

Libyan desert glass is a similar material thought to be caused by an impact in a sandy area. Fulgurite and the associated material known as lechatelierite are produced when lightning strikes the Earth in a sandy environment. These strikes instantly melt the sand, which then rapidly solidifies as amorphous silica. These materials are rapidly cooled glassy mineraloids.

Libyan Desert Glass is a yellow glass found scattered over the desert near the border between Egypt and Libya. It is believed to have formed in the seconds after an asteroid impact about 29 million years ago. Large amounts of desert surface were flash-melted by the heat of the impact and scattered over the surrounding land.

Psilomelane is a black hydrous manganese oxide that often contains barium and potassium. It is an amorphous material and an ore of manganese.

Mineraloid-forming Environments

Most mineraloids form at the low temperatures and low pressures found at Earth’s surface and in shallow subsurface environments. Materials such as opal, psilomelane, chrysocolla, limonite, and a wide variety of supergene materials crystallize from gels or colloids in the shallow subsurface. Many of these materials will eventually transform into minerals with time, heat, or pressure. These low-temperature mineraloids often have a mammillary (smoothly rounded or hemispherical), botryoidal (grape-like clusters), pisolitic (pea-like clusters), or stalactitic (icicle-like) habit.

Mercury is a liquid at room temperature, but when cooled to -38.8 degrees C, it crystallizes into a solid. Solid mercury meets all of the requirements of a mineral, and thus some people consider liquid mercury to be a mineraloid. Photo copyright iStockphoto / ados.

Limonite is an amorphous mineraloid. It is a hydrated iron oxide.

Water is considered to be a mineraloid by many mineralogists. It crystallizes into water ice when cooled to 0 degrees C.

Can Liquids Be Mineraloids?

Water and mercury are often classified as mineraloids. They are the only two natural inorganic substances that have a definite chemical composition and are liquids at room temperature. They are also the only two liquids that crystallize into minerals within the range of temperatures and pressures encountered at Earth’s surface. Water crystallizes into the mineral "water ice" when cooled to 0 degrees C. Mercury crystallizes into solid mercury at -38.8 degrees C. Due to the fact that they crystallize into minerals, some mineralogists include water and mercury in the mineraloids group.

Radiolarite is a sedimentary rock that forms from the accumulation of microscopic radiolarian tests and is thus of organic origin. This specimen is from the Windalia Radiolarite, a rock unit that formed on a marine shelf in an area that is now part of the Kennedy Ranges of Western Australia. When hard and tough it can be cut into cabochons, beads, tumbled stones, and other ornamental objects. It is sold as a gem material under the trade name "mookaite." Although it is a variety of chalcedony, some consider it a mineraloid because of its organic origin.

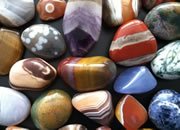

The best way to learn about minerals is to study with a collection of small specimens that you can handle, examine, and observe their properties. Inexpensive mineral collections are available in the Geology.com Store. Image copyright iStockphoto / Anna Usova.

Organic Mineraloids?

If you read information about mineraloids written by a variety of authors, you will discover that some authors include organic materials, such as amber and jet, in their list of mineraloids. Some mineralogists agree with such classifications, but others feel this stretches the definition of a mineraloid too far.

Amber is a fossil plant resin found in sediments and sedimentary rocks in many parts of the world. It is hard, brittle, translucent to transparent, and is often cut as a gemstone. It has the appearance of a mineral, but lacks an ordered internal structure and lacks a definite chemical composition. Furthermore, it is organic. It fails three of the five tests for being a mineral. Should it be called a "mineraloid"?

Jet is a rare type of dark black coal. It has a smooth texture that accepts a bright polish, which is why it is often cut as a gemstone. It has the outward appearance of a mineral but lacks a crystalline structure and a definite chemical composition. It is also organic. Should it be called a "mineraloid"?

A number of very tiny organisms, such as diatoms and radiolarians, produce a thin shell of amorphous silica known as a "test." When these organisms die, their tests sink to the bottom. When the tests are the dominant material that accumulates, the sediment is known as "ooze." If buried and lithified, the ooze can transform into rocks such as diatomite and radiolarite. If they are composed of amorphous silica, should they be called mineraloids?

| More Minerals |

|

Diamonds Do Not Form From Coal |

|

Tourmaline |

|

Tumbled Stones |

|

Rhodochrosite |

|

Gold |

|

Grape Agate |

|

Topaz |

|

Copper |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|