Crushed Stone - The Unsung Mineral Hero

It is the geologic commodity upon which almost everything is built.

Article by: Hobart M. King, PhD, RPG

Many types of crushed stone: Crushed stone is not a "standardized commodity." It is made by mining one of several types of rock such as limestone, granite, trap rock, scoria, basalt, dolomite, or sandstone; crushing the rock; and then screening the crushed rock to sizes that are suitable for the intended end use. The intended use also dictates which type(s) of rock should be used.

Crushed Stone: The Unsung Mineral Hero: Crushed stone is often looked upon as one of the lowliest of commodities, however it is used for such a wide variety of purposes in so many industries that it should be elevated to a position of distinction. It is the geologic commodity upon which almost everything is built. The word cloud above shows just a few of its diversity of uses.

"Unsung Mineral Hero" is a quote from the late Dewey Kirstein, Economic Geologist and one of the author's early supervisors. [7]

The Most Basic Mineral Commodity

Crushed stone is the world's most basic mineral commodity. It is abundant, widely available, and inexpensive. It is a material that people are familiar with in almost all parts of the world.

In 2020, the United States produced a total of about 1.46 billion tons of crushed stone [1]. That is an average of about four tons of crushed stone for each citizen. Most people have a hard time imagining how four tons of crushed stone were used in the past year for their benefit. That amounts to about twenty pounds of crushed stone per person per day for the entire year.

Most crushed stone is used in highway construction and building construction. In the construction of a two-lane asphalt highway, about 25,000 tons of crushed stone is used per mile. In building a small residential subdivision, about 300 tons of crushed stone is used per home [2]. Many other uses of crushed stone can be seen in the word cloud on this page. A larger list is included in the table near the bottom of the page.

Types of rock used to make crushed stone: The approximate amounts of different types of rock used to make crushed stone in the United States in calendar year 2020, when the total annual production was approximately 1.46 billion metric tons of stone. Data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) [1].

Rock Types Used for Crushed Stone

Many different rock types are used to make crushed stone. The types used to make crushed stone in the United States during 2020 include the following: limestone, granite, trap rock, sandstone, quartzite, dolomite, marble, volcanic cinder and scoria, slate, shell, and calcareous marl [1]. Their relative importance is shown in the pie chart on this page. Each of these rock types is suitable for a number of uses and unsuitable for others. A brief description of the more important rocks for crushed stone is provided below.

Limestone

Limestone: Crushed limestone of various particle sizes, from top left going clockwise: coarse aggregate, crushed limestone, mine run limestone, and limestone fines.

Limestone is a rock composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is the rock type most commonly used to make crushed stone in the United States. It holds this position because it is widely available and suitable for a greater diversity of uses than any other type of rock.

Limestone can be used to make cement. It is the primary ingredient of concrete. It is used as a base material for highways, rural roads, buildings, and railroad construction. It is used to make agricultural lime and for acid neutralization in the chemical industry. There are many products made from or using limestone that consume a small volume of material. These include poultry grit, terrazzo, glass, air pollution sorbents, mine safety dust, animal food supplements, cosmetics, dietary supplements, and blast furnace flux, whiting, among others.

In addition to its suitability for many uses, limestone is also used to make crushed stone because it breaks easily and is softer than the steel used in crushing equipment, classifying equipment and truck beds. Compared to harder rocks such as quartzite, limestone causes a lot less wear on the equipment that it comes in contact with.

As an example, imagine a truck loaded with 10 tons of crushed quartzite. Every piece of quartzite that is in contact with the bed and sides of the truck bed will have sharp points and edges. It will also have the pressure of all of the rock in the load above applied to it. When the driver raises the bed to dump the load, every piece of quartzite in contact with the truck bed will gouge a groove into the metal as it slides out the tailgate of the truck. The truck bed will become thinner with every load of rock that is dumped. Truck owners will not be happy when they have to repair or replace their trucks after a short time of use. Similar wear will occur on crushing equipment, screens, and every piece of equipment that contacts the stone. Now you know why mining companies would rather quarry limestone than quartzite.

Dolomite and Dolomitic Limestone

Dolomite (AKA "dolostone") and limestone are very similar rocks. Dolomite is a calcium magnesium carbonate (CaMg(CO3)2), while limestone is a calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Limestone is more effective for making cement and for neutralizing acids. Dolomite has a Mohs hardness of 4 compared to limestone with a Mohs hardness of 3. This hardness difference makes dolomite distinctly more durable when the rock is subjected to abrasion.

Dolomite, dolomitic limestone, and limestone have similar appearances and often occur together in the rock units mined at a single quarry; however, they are rarely mined as separate products. A significant amount of the material reported as "limestone" in the pie chart above is actually dolomitic limestone and dolomite.

Most quarries sell their production as "limestone," which is acceptable to customers in the construction industry if the chemical composition of the rock is not important. Customers interested in rock for chemical, acid neutralization, blast furnace flux or agricultural purposes will probably demand rock that has the chemical composition of a very pure limestone or a very pure dolomite.

Granite and Trap Rock

Crushed rock: Crushed igneous rocks of various kinds, from top left going clockwise: trap rock, white granite, lava rock, and red granite.

Granite is the layman's name used for any light-colored igneous rock that is used in construction. Granite, granodiorite, diorite, and rhyolite are a few of many light-colored igneous rocks that are called "granite" in the construction industry.

"Trap rock" is a layman's name used for any dark-colored igneous rock that is used in construction. Basalt, peridotite, diabase, and gabbro are examples of trap rock.

Granite and trap rock are the second and third most commonly used types of rocks for producing crushed stone. They are superior to limestone when used in acid waters or soils and when subjected to abrasion. They can substitute for limestone as a concrete aggregate and when a durable aggregate is needed.

Some geologists do not like how people in the crushed stone industry use the word "granite". That industry sells millions of tons of "granite" per year and has used the word "granite" in this way for generations. They are not going to change their terminology to satisfy a few picky geologists.

Sandstone and Quartzite

Uses of Crushed Stone |

|

| Road Construction | Macadam |

| Riprap | Jetty Stone |

| Filter Stone | Concrete Aggregate |

| Bituminous Aggregate | Railroad Ballast |

| Concrete Sand | Graded Road Base |

| Unpaved Road Surfacing | Terrazzo |

| Exposed Aggregate Concrete | Fill |

| Roofing Granules | Agricultural Limestone |

| Poultry Grit | Mineral Food Supplements |

| Cement | Lime |

| Dead Burned Dolomite | Blast Furnace Flux |

| Chemical Stone | Landscape Stone |

| Glass Manufacture | Sulfur Oxide Removal |

| Mine Safety Dust | Traction Stone |

| Acid Neutralization | Asphalt Fillers |

| Whiting | Fillers and Extenders |

Sandstone and quartzite are composed primarily of quartz, a very durable mineral, but each has its drawbacks in the construction industry that limits its use. Sandstone is generally composed of sand grains cemented together by calcite, clay, or silicate minerals that have precipitated between the sand grains. The cement usually does not completely fill all of the voids between the sand grains, leaving a porosity that typically ranges between 5 and 30%. This pore space allows the rock to absorb water. That water will expand in volume by up to 9% every time it freezes. Over the course of many freeze-thaw cycles, the forces of this expansion have the ability to dislodge grains and break the rock. This is why sandstone is not popular for long-term use in areas where freezing temperatures occur.

Quartzite is a sandstone that has been metamorphosed. The process of metamorphism heats and compresses the rock and often causes the sand grains to become welded together. This can produce an extremely durable rock that usually does not have the freeze-thaw concerns of sandstone. Quartzite can actually be so durable that it is difficult to mine, handle, and transport to construction sites.

Quartzite has a Mohs hardness of 7. That makes it harder than crusher jaws, loader buckets, sizing screens, truck beds, and other equipment used to handle and process the stone. As a result, it can quickly put very expensive wear and tear on essential equipment. For that reason, some of the most durable rock in the United States is avoided for construction use.

| Crushed Stone References |

|

[1] Crushed Stone: Jason Christopher Willett; Mineral Commodity Summaries; United States Geological Survey; January 2021.

[2] Crushed Stone Aggregate Overview: Division of Energy, Mineral and Land Resources; North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality; Undated website article last accessed May 2021. [3] Aggregate Protection Guidance: Eric Mears, Haley & Aldrich, Inc. (author); Arizona Rock Products Association (sponsor); 15 pages; April 2014. [4] Aggregate Sustainability in California: John P. Clinkenbeard and Fred W. Gius; Map Sheet 52; California Geological Survey, Department of Conservation; 35 pages; 2018. [5] Geologic Map Database for Aggregate Resource Assessment in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area and Surrounding Regions, Arizona: Philip A. Pearthree, Brian F. Gootee, Stephen M. Richard & Jon E. Spencer; Open File Report DI-43, Arizona Geological Survey, July 2015. Hosted by The University of Arizona campus repository. [6] Mineral Commodity Summaries 2021: United States Geological Survey; 204 pages, January 2021. [7] Limestone: West Virginia's Unsung Mineral Hero: Dewey Kirstein; an article in Mountain State Geology magazine, published by the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey; pages 25-28, 1984. |

Volcanic Cinder and Scoria

Volcanic cinder and scoria are vesicular rocks, meaning they contain voids that formed when gas bubbles were trapped within the rock as it solidified from a melt. These voids decrease the load-bearing strength and freeze-thaw durability of the material. However, the voids make the rock lighter. The surface roughness of the stone helps it bind effectively when used as a concrete aggregate. These properties often make volcanic cinder and scoria good rocks for producing lightweight aggregate, lightweight concrete, and roofing granules.

The lower density of volcanic cinder and scoria makes them easier to handle when used in landscaping, planters, gas grills, saunas, and other similar uses. The high surface area of these rocks makes them suitable for filter stone in some sewage disposal and drainage applications. Their angular shape and low density makes them suitable for use as a traction material that is spread on snow-covered highways.

Marble

Fine-grained marble and dolomitic marble can be crushed and used for most of the same purposes as limestone. When coarsely crystalline, these rocks often break into pieces due to cleavage, which can reduce their durability.

Some white marbles are pure enough that they can be crushed, processed to remove impurities, and used as chemical-grade stone, whiting, fillers, extenders, and even in cosmetics and dietary supplements for humans and animals. These high-purity marbles make some of the most valuable crushed stone.

Gravel: These pebbles, with rounded shapes produced by water transport, are what geologists would call "gravel." However, most people use the word "gravel" interchangeably for either "gravel" or "crushed stone."

Crushed Stone vs. Gravel

To a geologist, "crushed stone" and "gravel" are two distinctly different materials. "Crushed stone" is a commercial product made by mining rock and crushing it into angular pieces. "Gravel" is a natural material that consists of water-transported particles of rock that are larger than two millimeters in diameter and usually have a rounded shape as a result of their water transport. The shape of the grains and man’s role in producing them are the differences that separate crushed stone from gravel.

The average person in the United States rarely uses the term "crushed stone." Instead, the word "gravel" is used generically for almost any type of rock material with a particle size over a few millimeters. Their "gravel" includes both the crushed stone and the gravel of geologists.

U.S. crushed stone production: Value of crushed stone produced in 2015, by state. This map shows major production sites as black dots, and states are ranked according to their production of crushed stone on a dollar-value basis during calendar year 2015. The histogram across the bottom of the image shows the states in rank order. [6] [Enlarge]

Transportation, Imports, Exports

Crushed stone is a bulk commodity that is very heavy and very costly to handle and transport. In 2012, the average cost of crushed stone in the United States at the plant site was $9.75 per metric ton. Transportation to the job site can significantly increase the cost of the stone. At least 80% of the crushed stone produced in the United States leaves the plant by truck. Truck transport adds an additional 12 to 15 cents per ton-mile to the delivered cost of the stone [2]. For example, if the plant is 20 miles from the job site, the cost of transportation will be about $2.40 to $3.00 per ton.

Rail and barge transport have lowered costs per ton-mile; however, very few quarries are on rail lines or rivers. Most of the stone shipped by rail or barge must then be loaded into a truck for local transport. The cost of that handling can be an additional 30 to 50 cents per ton. For this reason, crushed stone is a commodity that is usually consumed locally as long as material that meets the job specifications is available.

Some metropolitan areas are a very costly distance from the nearest source of crushed stone. These cities are often served by distribution yards that receive crushed stone by rail or barge from distant quarries. This can significantly decrease trucking distance and provide stone to city consumers at a lower delivered cost.

Very little crushed stone is imported into or exported out of the United States. Transportation and handling costs are so high that less than 1% of the United States' domestic consumption of crushed stone is met by imports. With the exception of some coastal areas underlain by a broad plain of sediment instead of rock, crushed stone of suitable quality is locally available in most parts of the United States.

Recycled substitutes: Recycled substitutes for crushed stone. Starting at top left and going clockwise: crushed concrete, crushed construction rubble, crushed brick, and crushed gravel with asphalt.

Recycling

Throughout the United States, companies are recycling construction materials and using them as a substitute for crushed stone. The United States Geological Survey received reports from producers that approximately 30 million tons of crushed stone substitutes were produced through recycling in 2012. This annual number has been growing, but it is thought to be much lower than the actual amount of recycling that is done, due to non-reporting and recycling being done outside of the companies included in their annual crushed stone survey.

Used portland cement concrete from demolition sites is often taken to a quarry or to a distribution yard, where it is crushed, processed to remove metal, screened to size, and then sold as a crushed stone substitute. This material works well as fill, road base, and in other uses where the stone does not have to meet strict specifications. Recycling eliminates the need for a disposal site, and the product can be sold for 50 to 80% of the price of quarried stone.

Asphaltic concrete is often recycled by specialized paving equipment that can strip a road of asphalt and produce a crushed product that can be directly used at the job site. Used bricks and mixed brick/concrete waste are also crushed, sized, and sold as a crushed stone substitute.

Crushed Stone Production Graph: Crushed stone production trends for the last 100 years. Data from USGS [1]. Crushed stone production has generally been rising, with most of the drops caused by major or minor economic recessions. The dramatic rise began shortly after the Second World War when effective track equipment was developed.

Crushed Stone: Supply and Demand

The demand for crushed stone is driven by government infrastructure projects, commercial and residential construction, and other types of construction [1]. The line graph above on this page shows the trend of crushed stone production in the United States between 1921 and 2021.

Little crushed stone was used prior to World War II because it was very difficult to produce. However, after the development of durable track equipment (one of the few benefits of war), the production of crushed stone began growing rapidly. The growth has been interrupted by recessions in the general economy, shown in the chart as production drops of varying size. Currently, demand is still recovering from the Great Recession, but deferred infrastructure maintenance and projects could generate a large demand for crushed stone as the economy recovers.

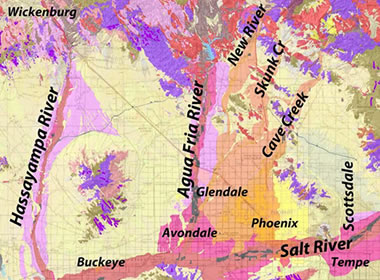

Aggregate Map: Simplified depiction of an aggregate resource map prepared by the Arizona Geological Survey for the Phoenix metropolitan area and surrounding regions. In this area, unconsolidated sands and gravels associated with stream valleys are a source of easily excavated and high-quality construction materials. [5]

| Photo Credits |

|

The photos of various types of crushed stone that appear in thumbnail size in the composite images on this page were contributed by a number of iStockphoto photographers.

In the top image, starting at the top left and going clockwise, the rock types and photographers are as follows: red granite, ru3apr; gray limestone, wuttichok; trap rock, Brilt; white granite, mmmxx; trap rock, mahout; limestone, wuttichok; vesicular basalt, heckepics; limestone, Nadanka; crusher run limestone, pookpiik; scoria, HIgs2006; limestone, pkanchana; and, limestone fines, wsmahar. In the recycled material image, the materials and photographers are as follows: crushed concrete, eyjafjallajokull; crushed construction rubble, daizuozin; crushed brick, sweetdreamsnov; crushed gravel with asphalt, Kritchanut. In the gravel image, the materials and photographers are as follows: brown gravel, aoephoto; light gravel, Martins Vanags. Each photo copyright by iStockphoto and the photographer. |

Aggregate Conservation

The United States and most other countries generally have an enormous crushed stone resource that, on the basis of its volume, might be considered inexhaustible. However, these significant resources are rapidly shrinking as buildings, roads and communities are built above them and land is made off limits to mining activity due to conservation, zoning, and local prohibitions.

Some communities have received rude awakenings when large construction projects that exceed the abilities of local crushed stone producers are approved, but the next-closest source of specification stone is 60 miles away. This can triple the cost of crushed stone, wreck the budget for the current project, and increase the cost of crushed stone for all future construction.

To avoid this, the crushed stone industry advocates identifying local crushed stone resources and setting areas aside for their development. If this is done, a local resource of crushed stone can be assured, and the cost of every future home, road, and construction project can be reduced [3] [4].

Some states realize the importance of aggregate conservation and require local governments to incorporate information about aggregate resources in their planning efforts. The Arizona Geological Survey prepared an aggregate resource assessment for the Phoenix metropolitan area and surrounding regions of Arizona to help local governments comply with state law.

"The Aggregate Protection section of the Regulatory Bill of Rights, SB 1598, of 2011 requires Arizona counties and municipalities revise their general plans to identify aggregate in their jurisdiction, and implement policies to preserve aggregate resources for future use by avoiding incompatible land use [5]."

They produced a generalized map that depicts the geologic units present at the surface that have been or are capable of being exploited for aggregate resources. Descriptions of these geologic units are included in their assessment. The assessment is available online where it can serve as a land management planning tool for local governments and as a source of reconnaissance data for aggregate producers [5].

| More Rocks |

|

Tumbled Stones |

|

Fossils |

|

Geodes |

|

The Rock Used to Make Beer |

|

Topo Maps |

|

Difficult Rocks |

|

Fluorescent Minerals |

|

Sliding Rocks on Racetrack Playa |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|