Emerald

The bright green gem of the beryl mineral family and May birthstone.

Author: Hobart M. King, PhD, GIA Graduate Gemologist

Emerald Crystal: A large (1,390-carat) prismatic emerald crystal with a deep green color housed at the Mim Museum in Beiruit, Lebanon. Photo by Cacoush, displayed here under a Creative Commons License.

What Are Emeralds?

Emeralds are gem-quality specimens of the beryl mineral family with a rich, distinctly green color. They are found in igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks in a small number of locations worldwide.

For over 5000 years, emeralds have been one of the most desirable and valuable colored stones. Ancient civilizations in Africa, Asia, and South America independently discovered emeralds and made them a gemstone of highest esteem. In the United States and many other countries, emerald serves as the birthstone for people who were born in the month of May.

Today emerald, together with ruby and sapphire, form the "big three" of colored stones. The "big three" generate more economic activity than all other colored stones combined. In 2015 the value of emeralds imported into the United States exceeded the value of all colored stones outside of the "big three" combined.

Table of Contents

Emeralds from Russia: Photograph of emerald crystals in mica schist from the Malyshevskoye Mine, Sverdlovsk Region, Southern Ural, Russia. The large crystal is about 21 millimeters in length. Photograph copyright iStockphoto / Epitavi.

Physical Properties of Emerald |

|

| Color | A distinctly green color that ranges between bluish green and slightly yellowish green. Stones with a light tone or a low saturation should be called "green beryl" instead of emerald. |

| Clarity | Almost every natural emerald has eye-visible characteristics that can be inclusions, surface-reaching fractures, or healed fractures. Treatments to fill the fractures with oils, waxes, polymers, flux and other materials to reduce their visibility has been common practice for hundreds of years. |

| Luster | Vitreous |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Cleavage | One direction of imperfect cleavage |

| Durability | Emerald is very hard, but almost all specimens have inclusions and surface-reaching fractures that compromise their durability. |

| Mohs Hardness | 7.5 to 8 |

| Specific Gravity | 2.7 to 2.8 |

| Chemical Composition | Be3Al2(SiO3)6 Emerald's green color is caused by trace amounts of chromium or vanadium. |

| Crystal System | Hexagonal. Often as prismatic crystals. |

Emerald's Green Color

Beryl, the mineral of which emerald is a variety, has a chemical composition of Be3Al2(SiO3)6. When pure, beryl is colorless and known as "goshenite." Trace amounts of chromium or vanadium in the mineral cause it to develop a green color. Trace amounts of iron will tint emerald a bluish green or a yellowish green color depending upon its oxidation state.

Emerald is defined by its green color. To be an emerald, a specimen must have a distinctly green color that falls in the range from bluish green to green to slightly yellowish green. To be an emerald, the specimen must also have a rich color. Stones with weak saturation or light tone should be called "green beryl." If the beryl's color is greenish blue then it is an "aquamarine." If it is greenish yellow it is "heliodor."

This color definition is a source of confusion. Which hue, tone, and saturation combinations are the dividing lines between "green beryl" and "emerald"? Professionals in the gem and jewelry trade can disagree on where the lines should be drawn. Some believe that the name "emerald" should be used when chromium is the cause of the green color, and that stones colored by vanadium should be called "green beryl."

Calling a gem an "emerald" instead of a "green beryl" can have a significant impact upon its price and marketability. This "color confusion" exists within the United States. In some other countries, any beryl with a green color - no matter how faint - is called an "emerald."

Be careful if you are buying an "emerald". Make sure that you are getting a gem that has a rich green color instead of a "green beryl". Buying from a website where people from outside of the United States are acting as third-party sellers and photographs might not have representative color can be especially risky.

Emeralds from Colombia: Emerald crystals in a calcite and graphitic shale matrix from the Coscuez Mine, near Muzo, northwestern Colombia. The well-formed crystal with an attractive bluish-green color is about 1.1 centimeters tall. Specimen and photo by Arkenstone / www.iRocks.com.

The Name "Yellow Emerald" Is Incorrect

By definition, emeralds are gem-quality specimens of the beryl mineral family with a rich, distinctly green color. Because of that, it is inappropriate to use the name "emerald" when marketing a beryl of any other color.

The Federal Trade Commission publishes a set of Guides for the Jewelry, Precious Metals and Pewter Industries. They use "yellow emerald" as an example of an incorrect name that when used in marketing can be "unfair", "misleading" and "deceptive" (the words here in quotes are straight from FTC guidance for jewelers). More information here.

If you are going to buy a "yellow emerald" it might be a good idea to compare it with an equivalent material that is properly marketed as heliodor or yellow beryl. Heliodor is a beautiful gem. It sells for a lot less than emerald and it usually does not suffer from the durability and clarity problems that are common in emeralds.

Emerald from Zambia: Emerald crystal from the Kagem Emerald Mine, Zambia, on a matrix of quartz and mica schist. This specimen is about 6.5 centimeters in height and has the blue-green color and medium dark tone that is common in many emeralds mined in Zambia. Specimen and photo by Arkenstone / www.iRocks.com.

Clarity, Treatments, and Durability

Emerald has a Mohs hardness of 7.5 to 8, which is normally a very good hardness for jewelry use. However, most emeralds contain numerous inclusions or surface-reaching fractures. These can weaken the gem, cause it to be brittle, and make it subject to breakage.

These are expected characteristics of emerald. It is rare to find an emerald that does not have inclusions and surface-reaching fractures that can be seen with the unaided eye. Under low magnification, most emeralds are said to have a "garden" of inclusions.

To improve appearance, most cut emeralds are treated with oils, waxes, polymers, or other substances that enter the fractures and make them less obvious. Although these treatments might improve appearance, they often do not improve the durability of the gem and they may discolor or deteriorate over time.

With that information, emerald should be considered a fragile stone that is best worn as a ring stone on special occasions rather than daily. Emerald is better suited for earrings and pendants that are usually subjected to less impact and abrasion than rings and bracelets. Settings that protect the stone are much safer than those that present the stone to impact and abrasion.

Cleaning emeralds should be done carefully. Steam and ultrasonic cleaning can remove oils and other fracture-filling treatments. A light washing in warm water with a mild soap is safer for cleaning and should be done only when needed.

Emerald imports: This graph illustrates the popularity of emeralds in the United States. The pie represents all colored stones imported into the United States during 2015 on the basis of dollar value. As a single gem variety, emerald holds the biggest share of the pie. More dollars' worth of emeralds were imported than any other colored stone. More dollars' worth of emeralds were imported than ruby and sapphire combined. Data from the USGS Minerals Yearbook, March 2018. [1]

Gemstone import value: This chart shows the quantity and value of diamond, emerald, ruby, sapphire, and other colored stones imported into the United States during 2015. This chart shows that, on the basis of cut but unset value, emerald is the most important gemstone import for the United States after diamond. It also has an average per-carat price that is much higher than ruby and sapphire. These amounts are approximately equal to consumption because the amount of domestic production was just several million dollars total. Data from the USGS Minerals Yearbook, March 2018. [1]

Geologic and Geographic Occurrence

Beryl is a rare mineral with a chemical composition of Be3Al2(SiO3)6. It is rare because beryllium is an element that occurs in very small amounts in the Earth’s crust. It is unusual for enough beryllium to be present in one location to form minerals. In addition, the conditions in which beryllium is present in significant amounts are different from the conditions where chromium and vanadium, the sources of emerald’s green color, are expected. This is why emerald is rare and only found in a small number of locations.

Today, most emerald production originates in four source countries: Colombia, Zambia, Brazil, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe. These countries reliably produce commercial amounts of emeralds. Minor amounts of production or irregular production comes from Madagascar, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Canada, Russia, and a few other countries.

Starting in about 2015, significant amounts of emerald with exceptional color and clarity started to be exported from Ethiopia. An editorial on the JCK website speculated that these Ethiopian emeralds might be the greatest gem find in 100 years. [2] An article in Gems & Gemology surveys the production of emerald in Ethiopia through 2017. [11]

Even though the conditions for the formation of emerald are very unlikely, the gem has been found in a diversity of rock types. In Colombia, the country that has supplied most of the world’s emeralds, black organic shale and carbonaceous limestone, both sedimentary rocks, are the ores for many emerald deposits. The shale is thought to be the source of chromium, and the beryllium is thought to have been delivered by ascending fluids.

Many of the world's emerald deposits have formed in areas of contact metamorphism. A granitic magma can serve as a source of beryllium, and nearby carbonaceous schist or gneiss can serve as a source of chromium or vanadium. These emeralds usually form in schist or gneiss or in the margins of a nearby pegmatite. Mafic and ultramafic rocks can also serve as sources for chromium or vanadium.

Emeralds are rarely mined from alluvial deposits. Emerald is usually a fractured stone that does not have the alluvial durability to persist great distances from its source. Emerald also has a specific gravity of 2.7 to 2.8, which is not significantly different from quartz, feldspar, and other common materials found in stream sediments. It therefore does not concentrate with high-density grains which are segregated in the stream and more easily recovered by placer mining.

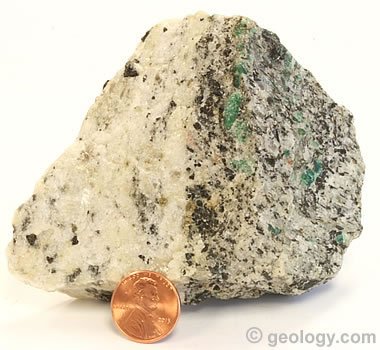

Emerald from North Carolina: A specimen of the Crabtree Pegmatite of western North Carolina. This granitic pegmatite filled a two-meter-wide fracture which contained emerald along the walls of the fracture and yellow beryl in the center. It was mined for emeralds by Tiffany and Company and a series of property owners between 1894 and the 1990s. Many fine clear emeralds were produced, but most of the emerald-bearing rock was sold as "emerald matrix" for slabbing and cabochon cutting. The cabochons displayed emerald and tourmaline prisms in a white matrix of quartz and feldspar. This specimen is about 7 x 7 x 7 centimeters in size and contains numerous small emerald crystals that are up to several millimeters in length and associated with schorl.

Emerald Mining in the United States

Very few emeralds have been mined in the United States. North Carolina has been a sporadic producer of emeralds in small quantities from a few tiny mines since the late 1800s. The Crabtree Emerald Mine was once operated by Tiffany and Company and a series of property owners between 1894 and the 1990s. Many fine clear emeralds were produced, and tons of emerald-bearing pegmatite were sold as "emerald matrix" for slabbing and cabochon cutting. The cabochons displayed emerald and tourmaline prisms in a white matrix of quartz and feldspar. A specimen of the Crabtree Pegmatite is shown on this page.

North American Emerald Mines operates a small mine near Hiddenite, North Carolina. Between 1995 and 2010, over 20,000 carats of emeralds were produced, including a six-inch-long, 1,869-carat crystal that is now in the Houston Museum of Natural Science and valued at $3.5 million. A crushed stone quarry on the same property is operated with employees watching for signs of the hydrothermal veins and pockets that sometimes contain emerald. It is one of the only gemstone mines in the world that sells the country rock. [3]

Trapiche Emerald: A photograph of a trapiche emerald crystal section. The green material is emerald, and the black is particles of the black shale matrix that were included during crystal growth. This photography by Luciana Barbosa is displayed here under a Creative Commons license.

Trapiche Emeralds

Trapiche emeralds are a rare variety of emerald that exhibit a six-sided, zoned morphology. Inclusions of their black shale matrix separate the growth sectors of the crystal. (See accompanying photo.) A cross-section through the trapiche crystals, cut perpendicular to the c-axis of their central core, resembles a wheel with six spokes. [4]

Trapiche emeralds are occasionally found in a few mines on the west flank of the Eastern Cordillera Basin of Colombia. They are thought to form when fluid overpressuring, followed by sudden decompression, causes rapid crystallization of emerald. During this rapid crystal growth, particles of the black shale matrix are trapped between the six growth sectors of the emerald crystals. This is the origin of the six black spokes of the wheel.

Synthetic emerald: The materials in this photo are lab-created or synthetic emerald produced by Chatham. On the left is a faceted synthetic emerald weighing 0.23 carats and measuring 5.1 x 3.0 millimeters. On the right is a synthetic emerald crystal weighing 2.0 carats and measuring 8.1 x 6.1 x 4.9 millimeters.

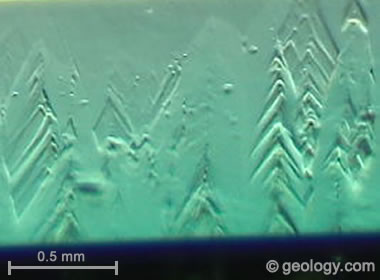

Evidence of Synthetic Origin: Microscopic examination is the best method for separating synthetic emeralds from natural emeralds. The photo above show chevron-type growth zoning in a synthetic emerald grown by the hydrothermal method.

| Emerald Information |

|

[1] 2015 Minerals Yearbook - Advance Data Release: Gemstones: Donald W. Olson; The United States Geological Survey; 2018.

[2] The Greatest Gem Find in 100 Years?: Victoria Gomelsky; JCK Online Blog; April 16, 2018. [3] Emeralds: Fred Ward; Fred Ward Gem Books; third edition; 64 pages; 2010. [4] Colombian Trapiche Emeralds: Recent Advances in Understanding Their Formation, by Isabella Pignatelli, Gaston Giuliani, Daniel Ohnenstetter, Giovanna Agrosì, Sandrine Mathieu, Christophe Morlot, and Yannick Branquet; Gemological Institute of America; Gems and Gemology, Volume 51, Number 3, pages 222 to 259; Fall 2015. [5] Gems: Their Sources, Descriptions and Identification: Michael O’Donoghue; Elsevier; sixth edition; 873 pages; 2006. [6] Gemstones of the World: Walter Schumann; Sterling Publishing; fifth edition; 320 pages; 2013. [7] Emeralds: A Passionate Guide: The Emeralds, the People, their Secrets: Ronald Ringsrud; Lith Publishing; 382 pages; 2009. [8] Rock and Gem: Ronald L. Bonewitz; The Smithsonian Institution, Dorling Kindersley Publishing; 360 pages; 2008. [9] Big Crabtree Emerald Mine: Spruce Pine District, Mitchell County, North Carolina, USA; Mindat.org; accessed July 2014. [10] Guides for the Jewelry, Precious Metals, and Pewter Industries, proposed revisions; Federal Trade Commission; 16 CFR Part 23, 2015. Link to excerpt. [11] A New Discovery of Emeralds from Ethiopia, by Nathan Renfro, Ziyin Sun, Michael Nemeth, Wim Vertriest, Victoria Raynaud, and Vararut Weeramonkhonlert; Gemological Institute of America; Gems and Gemology, Volume 53, Number 1, pages 114 to 116; Spring 2017. |

Synthetic Emerald

The first synthetic emeralds were produced in the mid-1800s, but it was not until the 1930s that Carroll Chatham began producing synthetic emerald in commercial quantities. Once commercial production began, a steady supply of synthetic emeralds began entering the market.

To date, several companies including Chatham Created Gems, Gilson, Kyocera Corporation, Lennix, Seiko Corporation, Biron Corporation, Lechleitner, and Regency, have produced synthetic emeralds by flux and hydrothermal processes. [1]

Synthetic emeralds, also known as lab-created emeralds, have the same chemical composition and crystal structure as natural emeralds. They are sold beside natural emeralds in most mall jewelry stores in the United States. When compared to natural emeralds, the synthetics typically have superior clarity and a more uniform appearance than natural stones of equivalent cost.

There is nothing wrong with synthetic emeralds, or synthetic stones of any kind - as long as their synthetic origin is clearly disclosed to the buyer. They are simply another option for the buyer. Many consumers purchase synthetic emeralds and enjoy them because they obtain superior appearance at a substantially lower cost.

The two key tests for separating natural emeralds from synthetic emeralds are refractive index and magnification. Natural emeralds generally have a refractive index that is slightly higher than most hydrothermally produced synthetic emeralds and much higher than most flux-grown synthetic emeralds. These differences are not large enough to be relied upon for important determinations; however, they can serve as a valuable indicator.

Magnification is the most important tool for separation of natural emeralds from synthetic emeralds. Synthetic emeralds can often be identified because they contain visible characteristics that are a product of the techniques used to create them.

Hydrothermal synthetic emeralds might display characteristics that include: chevron-type growth zoning, nail-head spicules, and small gold inclusions. Flux-grown synthetic emeralds might display characteristics that include: wispy veil inclusions, tiny platinum crystals, or parallel growth planes.

Many gemologists can quickly identify most synthetic emeralds by microscopic examination.

Green gemstones: A collection of green faceted stones of various types. Most of them are not emerald. If you want a green gemstone, which one would you choose based upon color and appearance?

Beginning in the back row at left - the name of the stone and its locality, carat weight, and the price that we paid: 1) chrome diopside from Russia, 1.16 carats ($11); 2) green quartz (dyed) from North Carolina, 2.6 carats ($8); 3) green tourmaline from Brazil, 0.77 carats ($58); 4) lab-created emerald manufactured by Chatham Created Gems, 0.23 carats ($37); 5) emerald from the Crabtree Mine, North Carolina, 0.50 carats ($80); 6) emerald from Colombia, 0.53 carats ($112); 7) tsavorite garnet from Tanzania, 0.68 carats ($105).

Notice how some of the least expensive stones are free of eye-visible fractures and obvious inclusions, while costly emeralds have fractures and inclusions that are clearly visible with the unaided eye. Some people have such a high desire for "emerald" that they are willing to pay more for an emerald than for another green stone that is larger, cleaner, and more attractive. Buy what you like!

Imitation Emeralds

"Imitations" are materials that have a similar appearance to natural gems and are used in their place. They are often manufactured specifically to serve as substitutes.

Green glass, synthetic green spinel, green cubic zirconia, and green yttrium aluminum garnet are common imitations used in place of emerald.

Emerald Alternatives

"Emerald alternatives" are other natural stones with a green color that are purchased by people who simply want a green gem. They might prefer to own an emerald, but they select the alternative stone instead because of its lower price or other characteristics.

Chrome diopside and chrome tourmaline are deep green gems that some people purchase when they want a green gem. Tsavorite garnet is another gem with a wonderful green color. Dyed quartz can be a beautiful stone at a very low cost.

Several examples of alternative stones and synthetic emerald are shown in the nearby photo. The best rule for buying gemstones is: "Buy what you like!"

| More Gemstones |

|

Tourmaline |

|

Fancy Sapphires |

|

Diamond |

|

Canadian Diamond Mines |

|

Birthstones |

|

Pictures of Opal |

|

Fire Agate |

|

Blue Gemstones |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|